From the Archives: Sick Day

From the archives: as we head into 2024, we are featuring some of our magazine’s earliest publications. This piece was originally published in issue number one.

Cheng leans over my right thigh, shaving the baby hairs from the elastic band of my panties down to the middle of my quadriceps. In private school, that was the highest the hem of my skirt could go, the bottom of my fingertips. I’d wished then that I had shorter arms. I could have had shorter skirts and garnered more male attention. Unfortunately, I was appropriately proportioned; my skirts would go no higher than the inch above my knee. I haven’t worn a skirt in years, and I didn’t think about male attention until now.

The morning Marcus left; I went to Labuha on my own. Nobody asked about Marcus, but they knew. People treated me gingerly. They kept insisting that I not work so hard. That I take some rest. When Ray, my boss, said that I was due for a break and sent me home early, I knew that Marcus had called and told them he quit. That he was going home to terra firma. The orientation for the International Med Corps includes the pessimistic fact that there is an expiration date for people in disaster work. Everyone spirals out, eventually.

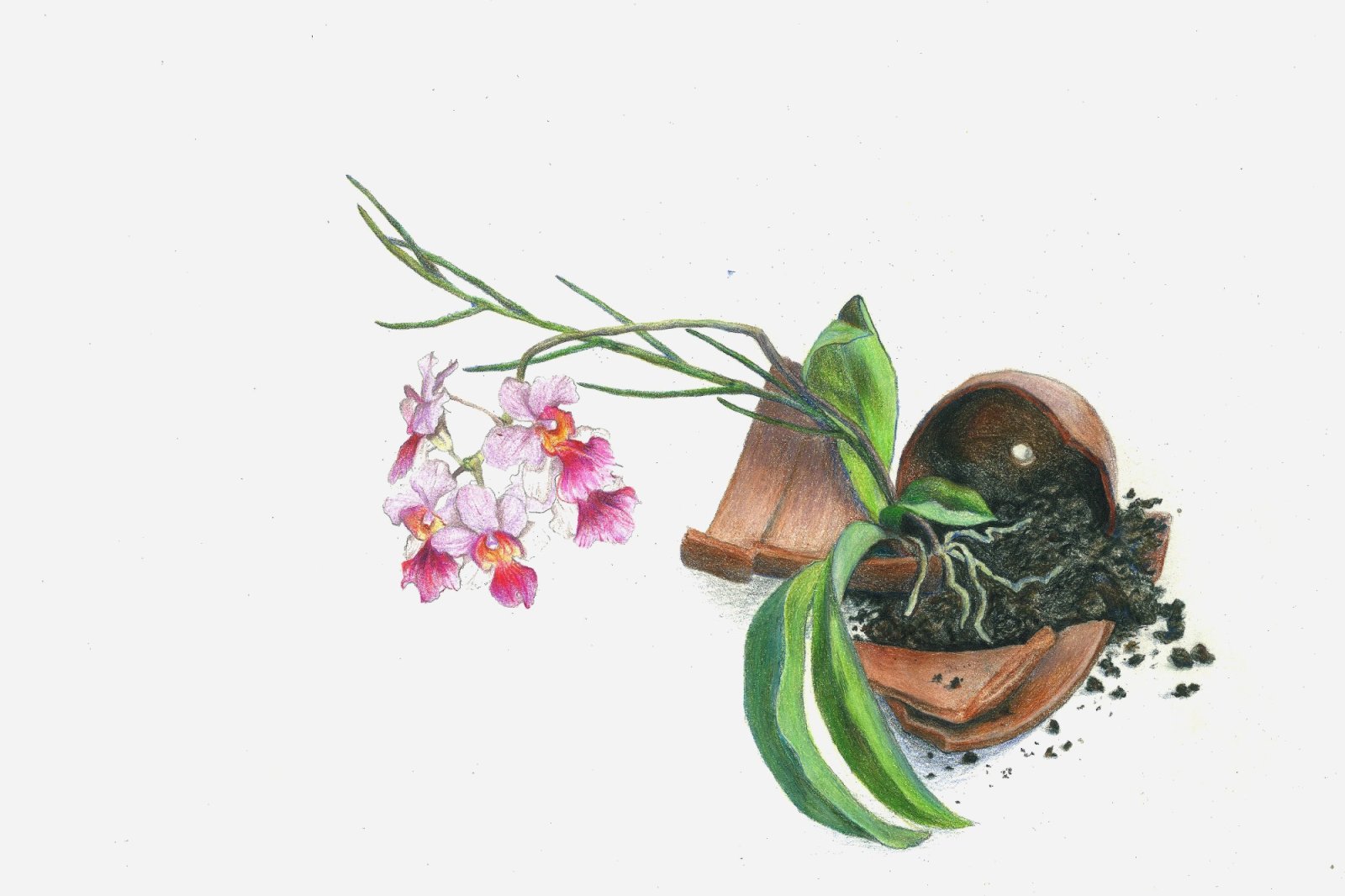

I feel the pulling of the cheap plastic razor against my damp skin as Cheng guides the white and yellow instrument down my thigh one more time. There needs to be no hair or the design won’t lay properly. He glides deodorant—men’s Speed Stick—over the area. I know that ice blue color. I know that smell: eucalyptus and sage. Marcus. Even here, in a tattoo parlor in Singapore, I can’t get away from him. The tracing paper crinkles as Cheng presses it onto my skin. It’s a Vanda Miss Joaquim, an orchid with large, broad violet-rose colored lips that feeds into a fiery orange mouth.

In high school, there was a Revlon lipstick shade that we were all dying to be allowed to wear: “Hot Lips.” A Magenta pink shade just verging on scandalous red. I remember that the morning Marcus left I was “hot lips” everywhere. Burned by his stubble across my breastbone and down my clavicle. He’d marked my body. And I had marked his. The indentations of my teeth were still in his shoulder and there were light claw marks near his groin. When we turned on the news, the footage of the quake was everywhere. A 7.3. It struck near one of the small port towns in the Bacan Island. We knew there was going to be damage. Fatalities. Chaos. We’d seen it before. Marcus clicked off the devastation, making the TV a vacant black square, “I can’t go to another one. I can’t work another one.” He was hunched over in defeat. “I just can’t.” I had already put my daisy scrub shirt on.

Singapore’s national flower, the Vanda, has a vibrant, almost hidden, sunny yellow core. I stare at it while Cheng works. I like that he is quiet, efficient, and methodical. He is an artist and precise in his choices. We all make our choices. I take a moment and look down to see what he has drawn on me. There are six buds on two clusters, not one is facing out. This gives the illusion of depth. But to see Vanda, I’ve moved my body, Cheng’s canvas, and he sits frozen with a permanent marker in hand waiting for me to return to an anesthetized-like state. I lie back down and look away. My cheeks flush. He caught me looking when I had said I didn’t care. I feel the tip of the marker press into my skin, making quick vertical strokes and then some light hash marks. It’s wet, like tears or sweat.

I remember wet. I remember sweat the day that Marcus left me, but I don’t remember the exact moment.

It was 92 degrees that day, hot for an Indonesian summer and it rained 4.7 inches. The North Maluku Earthquake had just shaken the island like a coconut tree, and he was there and then he wasn’t. I can’t remember if I cried. I remember the other people crying, I remember rounding and rounding and rounding, seeing patient after patient after patient, crying, scared, bleeding, bruised. When working a disaster, narrow your focus to the patient, the person in front of you, the handbook advises their doctors. Treat and move on. Treat and move on. Time stretches and shrinks that way. Hours pass in the blink of an eye.

Cheng catches me looking again. He must sense the concern I have about the large number of hash marks he’s added to the background. From here, it looks like a large black box, a coffin. This isn’t what I pictured.

“You need contrast,” Cheng says gesturing to the unmarked area and my overall lack of pigment. I lie back down. I hear the buzzing of the gun begin. He is testing it out, adjusting the speed of the needle. Then he’ll dip the needle in a pool of black ink smaller than my pinkie nail, rest his hand on my thigh, and press the needle into my skin. I expect it to hurt.

Marcus had threatened to leave many times and, eventually, it was going to happen. He wanted solid ground. But I was going to go where the earthquakes were. He couldn’t be in a constant state of fluctuation any longer. Certainty was critical. When we argued, it was always the same. “There’s always going to be another earthquake, Gina,” he would say, “This is fucking Indonesia!” And I would shrug. We would go to bed. We’d make out, his beard stubble burning my chin as it rubbed me raw. In the morning, it would be the color of Rainer Cherries. He told me they called it a “pash rash.” Back home, it was something to be proud of because it was a mark of the loved. Those Aussies have a language all their own.

I should be embarrassed by my body and its condition. I see that there are saddlebags forming in the vicinity of Vanda. Masses of cellulite bubble up under the skin as Cheng leans on my naked thigh. I used to work out every Tuesday and Thursday when I lived in the States. Here though, it’s hard to have a schedule when you are jumping from place to place whenever the phone rings or the ground shakes. When Cheng asked where I wanted the piece and I dropped my pants to show him, I began to remember my body. I hadn’t shaved anything in my southern or northern hemisphere in months. Now, there was a new man crotch-level and I didn’t know which kind of underwear I had on, the utility or the pretty kind? Cheng was professional. He didn’t balk at my condition. He was steady and calm. Like he is now, his whole body leaning over my exposed flesh. Every scar and hair visible. He doesn’t notice what’s on the surface, he is focused on implanting something deeper down. It relaxes me that he’s so engrossed in his job. I understand that tunnel vision. I relax my quadriceps and slow my breathing. He is looking not at what is there but at what will be there. Craning my neck, I see that he has finished the outline of each delicate petal. It’s odd, childlike almost. It’s hard to differentiate one form from another without color. I hope this wasn’t a mistake.

I never thought it was a mistake to follow the quakes. The first time was the day after Christmas in 2004. I still remember, fifteen years later, when the short news blip talked about mass fatalities after a 9.3 earthquake near Sumatra and the resulting tsunami waves. My mom was in the kitchen heating up leftovers and planning the New Year’s Eve menu. My dad was fussing with the logs in the fire. My brothers—home from college—were flipping the TV on to catch the Patriots vs. the Jets when we saw the 15 second coverage.

“We should donate blood,” Ryan said.

“Maybe tomorrow,” Chris replied, holding up his beer as proof of his ineligibility.

“Such a shame,” my dad said, sitting back in his chair. “What time is kick off?”

“Weren’t the Parkers going to Indonesia, Ted?” my mom asked, pulling the gravy boat out of the microwave, using the crocheted potholders that Aunt Sally made. “Phuket, does that sound right?” she asked, concentrating on setting the hot ceramic on its matching dish.

“That’s in Thailand, Mom,” I corrected her.

“Well, waves travel far, Gina,” she replied.

Cheng is going over and over the punctured areas of my skin with his gun and wiping the droplets of blood away as they appear. It didn’t hurt at first, but it does now, in the middle, as he adds layer upon layer of pigment, deepening the color, getting under the next layer of skin. Each injection is a pinprick of pain, short and electric. The paper towel is like sandpaper. I am usually the one in control, the one working, the one in charge of someone else’s life, their body, and appearance. But here at Singapore Electric, Cheng is taking charge of my body, my appearance, my life. His brows are deeply furrowed, concentrating on applying the varying shades of magenta. My skin has been rubbed raw by the repetitive movements. I wonder if my thigh is the color of “hot lips.” I assume it is. I wonder too, how Cheng can tell the difference between the color he is injecting and the color I have become.

I met a tattooed Mentawai woman in September of 2007 after her granddaughter helped her escape the tsunami waves from the series of earthquakes that had hit near the islands. She had blue dots running up her hyoid bone, dashes that encircled her radius and ulna at the wrist joint and vertical lines that exploded from a ball at the center of her hand that ran with her arteries. She was one of the last remaining fully tattooed people from her culture. She grabbed my left hand and examined the black marks left by my life-long habit of impatient pen tapping just below my index finger joint. When she rubbed them, they faded but remained slightly visible. She covered my hand with hers and tapped it twice. She met Marcus, too. I think she liked him better than me because she kept rubbing the black and grey eucalyptus leaves tattooed on the posterior side of his bicep. When they didn’t fade, she smiled despite the agony of her cracked ribs.

I knew the acute pain would recede when the area went numb, I just hadn’t realized how long that would take. Cheng had to stop when I began shaking. He was filling in the stems with a lime green hue. A canvas shouldn’t move. I was grateful Cheng didn’t say anything. The new growth on my leg is attention grabbing. It is vibrant and prominent. The thick black lines are rimmed with an imperceptible white one. I thought the white wasn’t going to show up on me. I thought it wasn’t going to have an impact. But the contrast gives the green a lushness that it didn’t have in the jar. We aren’t done yet, though. There is still the background. Cheng sits and motions that he is ready to begin again. I feel his hand lightly tracing the hash marks. The vibration of the gun is more violent than the pressure on my skin.

Yesterday, just before Ray forced me out the door, he made sure to tell me that, “Australia is nice this time of year and just a short skip away.” I am sure that when I called in sick today, that’s where he thought I went. Everyone expected me to chase after Marcus. Everyone wants us to be together. We were something concrete and predictable.

At the beginning, Marcus and I looked like a probability. It was likely we would last. We both wanted variability, not volatility. We both appreciated the thrill of the unknown, loved the challenge of rapidity, and hated the possibility of mortality. But somewhere along the way our relationship suffered structural alteration caused by a growth. Marcus’ growth. He no longer found the dynamism of sporadic, but consistent, calls to arms romantic. He was no longer attracted to the quick fix or fixing quickly. There is only one solution for a growth: removal. He made the incision, but I am responsible for sending the specimen down to pathology and suturing and dressing the wound.

When Cheng finishes, he is sweating and wipes the side of his face with the hem of his t-shirt. He covers Vanda with a sheet of cling wrap and tapes it in place. She can’t be shown until she is ready. He suspiciously eyes my pants as I pull them back on and then nods approval. They are hospital scrubs. Baggy and loose. They will not constrict or suffocate Vanda. As I hand over my credit card, I’m hit by a wave of unexpected sadness. Cheng must see it on my face.

“They are my favorite thing to tattoo on women,” Cheng says. “Orchids.” He was the one to recommend Vanda to me. I’d been considering lilies or maybe even carnation, but he was insistent. An orchid. This orchid. “Many are beautiful. Some are delicate. But they are all resilient,” he continues while shuffling the papers on the counter-top. “Orchids defy expectation.”

I smile wide. “That they do.”

On my way out of the door, I call Ray and see if they need any help. If I hurry, maybe I can make the evening shift. I crinkle as I walk and there is a tightness around the damaged skin, but I feel a buzz of adrenaline, Ray was surprised and reluctant but said they could use always use the help. Just get here when I can.

Suggested Reading

-

Featured • Fiction

-

about Lollipop, Lollipop![Lollipop]()

Featured • Fiction • Nonfiction

Lollipop, Lollipop

The figure moved slowly, deliberately, its shrouded head turning towards Josh. Those eyes—sharp and frigid as icepicks—stared at him. The man’s black lips never moved, even as a word pierced him like a yell: “Beware.”

Featured • Fiction • Nonfiction

-

Featured