Perdition

I.

“I know if I hack open my father there will be a black ooze that will come out. It will gush, first reaching toward me before spilling onto the floor. It will keep pouring. If there is anyone to come across it later, they would wonder from where it all had come.”

Katarina stares forward. After a pause, she nods. She accepts it. I hope she does. It wouldn’t matter now. I said it; she seems distant. I tear my hand away from hers and plop it in my lap. I don’t want her to know I am afraid.

The small grassy mound where we sit is between Blue Ridge River and Blue Ridge Road. Blue Ridge Road is the main road out of Perdition and leads right to the highway. Blue Ridge Road has a sharp, high turn just above us. Regularly, trucks, cars, and motorcycles take the turn too fast and don’t make it. They tumble down the 50 yards toward the river. This patch is hidden with a row of trees and bushes purposely planted to prevent people from wandering here. The other side has a fence and a gate. My father has a key, having been hired by the city of Perdition to come and clean up the wreckage whenever it happens.

Katarina and I unlock the fence and sit near the water. She leans against me. We don’t speak after my confession. We listen to the traffic above us, which easily drones out the lapping river. I don’t tell her about the dog. I won’t say anything unless she asks. Tires above us scream. We turn to look up and see a car rub the steel rail above us. Sparks fly and we anticipate a crash that doesn’t happen. A grim smile stretches across her face and she grabs my hand.

“That was close.”

“Yeah.”

“I think my mom has it, too.”

“Yeah?” I’m not surprised, convinced most have it now.

“I think maybe both my parents.”

“Let’s leave, ” I say, surprising myself as the words escape before I can catch them.

“Where?” she asks, unable to hide the burst of laughter. Then she shakes her head no and sighs, “I don’t know.” Tears well behind her eyes and the sadness seems to stretch out forever. “Thad…” But she doesn’t say anything else. She presses her face against my chest. We both fall to silence. She pulls her hand from mine and reaches into her pocket for a tissue to wipe her face and then pushes the tissue quickly back into her pocket.

The clouds move, allowing the sun to peer through. I feel blinded. The sun is especially bright after hiding behind the clouds all day. Katarina shields her eyes until the sun creeps behind another gray cloud. The wind blows, causing the grass, trees, and bushes to bounce back and forth slapping against each other.

“I don’t think I’ve seen the sun in over a week. It’s been…”

“Rather tragic.”

“Could it be linked to…?” My mind draws connections to what I don’t want.

“I don’t know, Thad. It’s probably sunny in Florida or some tropical place.”

“We can go there.”

We lapse into silence, thinking about distant beaches and palm trees, a happy sun shining down on children running into the surf. Then, in my mind’s eye, clouds fill the sky and the ocean turns black. As the waves lap the shore. It isn’t water; it’s the ooze.

I shudder.

“What?”

“Nothing.” I can’t tell her.

“I wish I had one of those phones to look up the weather in Florida.”

“Yeah.” And in a poor Russian accent, “And the weather in Moscow!”

She giggles. I lean in. Our noses rest briefly against each other as our lips caress. Then we hear screeching brakes.

I stand without hesitating. Katarina leans forward to unhook her leg. I don’t wait. I grab her shirt and drag her upward, pushing her in front of me as a semi-trailer with a moving company name bursts through the metal rail. Katarina turns to look. Everything slows down. We’re moving, but could be standing still. The trailer slowly begins its tumble. The first smash against the scattered large rocks imbedded in the ground bursts the trailer open. Everything flies outward. Boxes and furniture become shrapnel. I push the door to the fence still clutching Katarina’s hand and we fall to the other side.

The grass looks dead. I hadn’t noticed it before. Everything is dying. Winter is on the horizon, a time when everything dies. I look at Katarina, and she’s already turning around. She’s smiling.

I survey the wreckage. The trailer lays in pieces. Boxes and furniture are spread across the grass in front of us. I think of my father torn open as I see the broken trailer, like a torso spilling its intestines. I follow Katarina who rushes toward the front cab.

I freeze, knowing I see it first. It stares at me. The familiar look as if it remembers. Perhaps it does. A smear on the windshield, not of blood. I wish it were blood. But I know the ooze is stretched across the windshield and out through the broken glass into the dirt and dead grass.

“Is it moving?” she asks.

I don’t want to look at her. I don’t want to turn my head away from it. I try to move my feet. I feel the warmth of her hand wash over me. I see it, the ooze stretching out, before stopping.

“No. It’s not. I thought at first, but not now. Maybe it was just pooling.”

She knows I’m lying. It would’ve headed downhill not uphill toward us if it was really pooling. We can see inside the cab, the ooze-filled shell is dead.

“My parents’ house is closest. We’ll go and call it in,” I try, pulling her back.

“Do you think….”

“If there is anyone without infection, more will become aware. At least now there’s proof, right?”

She lets go of my hand, and I follow her to the fence. I decide to leave it unlocked so the cops can easily access the scene. As we head toward my house, I wonder if we really should call anyone. I wonder if anyone can help us now.

II.

We walk along the familiar trail, the trees hiding us from the sky. We don’t speak. The clouds above thunder once, but no rain. When we get to the field, I hesitate. My house looks abandoned.

When we get closer, I run in, but Katarina stays outside. Staring at her, I lift the phone. Three rings before the line goes dead. I set it on the receiver. Katarina still looks at the field. I approach her, and even though I want to put my arm around her, I don’t. She grabs my hand and squeezes.

“The line went dead.”

She knows.

We don’t speak as I linger, expecting someone to call in the accident. My father was in charge of cleaning the stretch. Someone should be calling and giving orders. Someone should be reaching out soon. The whole world is reverting into itself.

“I’m going to go back,” I tell her.

“Take me home?”

The old pickup starts and shakes as I reverse. It no longer looks red. The paint and rust have made it a dusty gray. We don’t speak. She’s lost in thought. If she wants to say something, she will. I drive down the farm road and see her family’s farm ahead. Trees scatter on one side of the house, next to a large barn. We pull around into her driveway. The barn now obscures her house. Her mother is in the yard hanging a sheet on a clothesline. She doesn’t acknowledge us.

Katarina smiles, but it feels distant.

“Are you okay?” But when she doesn’t speak, I say, “Stay with me.” I’ve never asked this. I want her to stay. I want us to leave together. I want us to run away to a city or somewhere else. I want to be free. Freedom is with her. She reaches for my hand, grabbing it, holding it tightly. Still, she doesn’t say anything. I repeat in a breathy, desperate tone, “Stay with me.”

“I’ll see you tomorrow?”

The road is falling apart, and the truck shakes violently as I drive twenty miles an hour back to the Blue Ridge crash. Before, my father and I would’ve dropped her off together. We would have driven to the site together to survey it, making notes of what we needed. We would even scavenge what we could. But now he is at our lifeless farm. He only appears at night, acting strange and distant. No longer the kind man I knew, but turning into something else.

When I was thirteen, the land quit yielding crop. This spread around the area gradually until dead fields surrounded the Blue Ridge area. It looked as if Perdition would become a ghost town as many farmers abandoned their land and moved away. My father’s farm was the first. He sold some land to keep us going. Then a friend of his arranged the Blue Ridge clean-up project. Between that and my mother’s job, we’ve barely kept afloat.

Whenever a crash happened at night, my father would wake me early. The sun wouldn’t have risen, but I have never known my father to sleep past sunup anyway. Not until the ooze. Now, he sleeps at odd hours and odd times; locking himself in his room doing whatever.

Once, we drove the same pickup onto the grass to look at a crash site to see what we would need. The sun rose, glistening dew on top of large black leather bags laying all over the hill. The truck lay on its side with a cold mist coming out of the open back door. My father crouched down and found a zipper. It was a body. I stepped back seeing the pale face, but my father didn’t react. He didn’t hesitate. He zipped the bag up and nodded.

“We have to get the bodies quickly before they start smelling.”

I spent that morning thinking about his nod of resignation. This is my job. This is what I have to do to provide for the family. But now I wonder if it was just a nod. I see that nod every day. My father, usually after sunset, wanders the hallways of our house, his head bouncing up and down as if he’s listening to someone talking. Then he mumbles to himself, a rambling sound as if trying to reach out from deep inside a tunnel.

Now, I walk around the crash site with a clipboard and look at the boxes tossed everywhere. It’s the same routine. We’ll need a tractor to move the truck. I grab a box of family photos and toss it in the truck before anything degrades the box more. The rest I leave for later. We store everything in our barn for the family to come and see what they want to salvage.

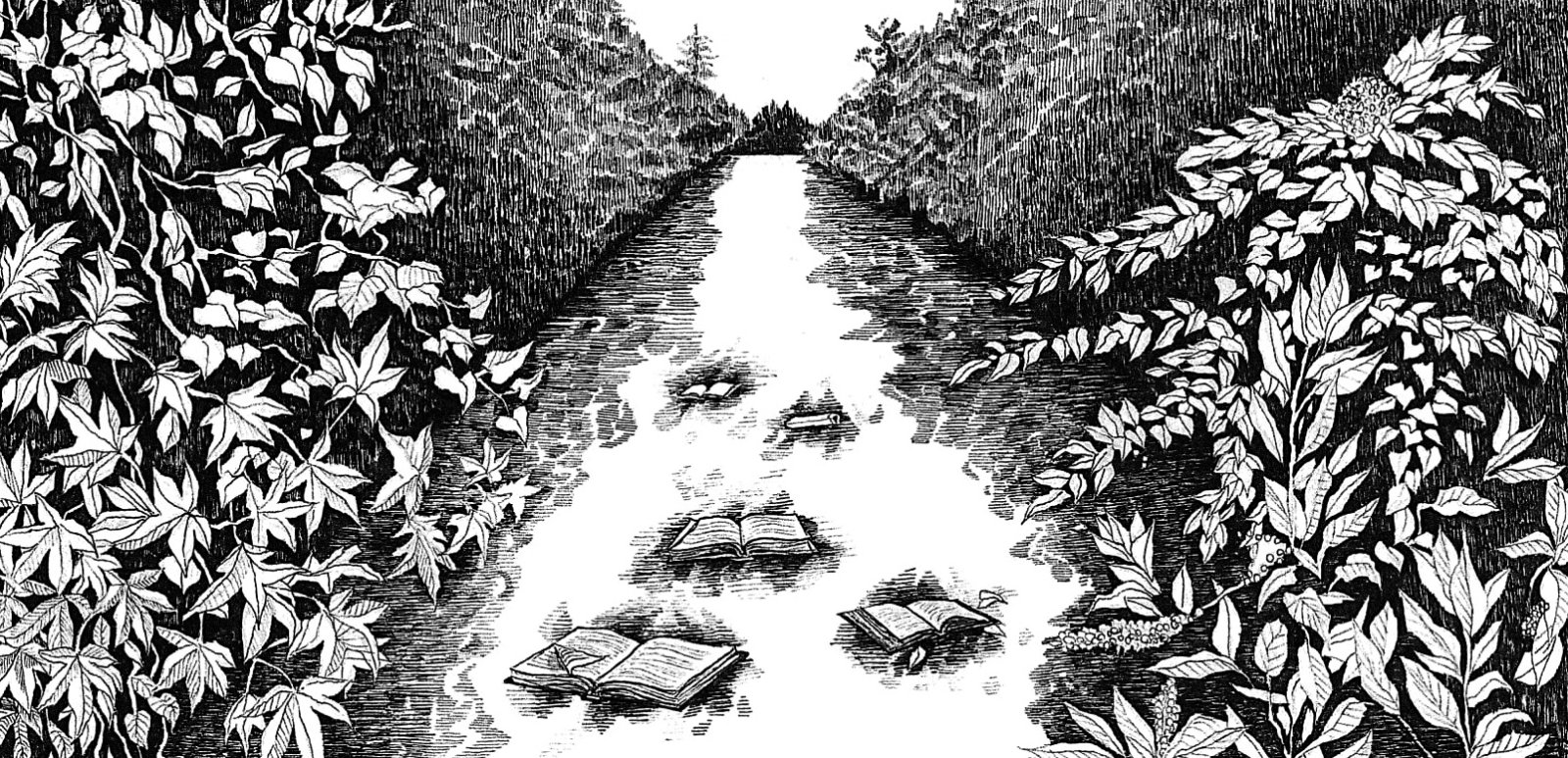

I walk up to the riverbank. One of the boxes is broken open. Books spill out along the river and float. I find myself looking at the different titles. One close to my feet lags half in water and half out. I pick it up and see the words washed away from one of the pages. I leaf through the book, briefly seeing whole chapters ruined, lost to the river. The book, forever changed, now possessing a different story. I wonder if this is what the ooze was doing to people; rewriting everything, editing the universe one person or even one planet at a time.

At night, I sit in my room with the lights out to see if my father or mother will notice I’m not around. My mother is a phantom in the house. They used to check my room to see if I was home. I can hear him pacing outside my door up and down the hallway. He’s humming a rhythmic tone and steady beat that goes nowhere.

I open the door. The hallway has his smell. His back is turned to me. I miss him. On the surface, it looks like my father. He freezes hearing the door open.

“Dad?”

He doesn’t move. He stops humming.

“There was a wreck this afternoon.”

A loud hum comes out of his throat. My stomach turns hearing his voice so clearly. Is he still in there? How long has it been since we’ve spoken?

“Should we go to clean it in the morning?”

In the past, he would’ve asked if they had called. He would have asked for every detail. In the past, he would have acted so differently. Now, he seems almost afraid. He doesn’t turn around. I hide in my room again, not wanting to see his face. I am not strong enough to see his face.

The pacing resumes when my door closes. The moonlight is bright enough, so I don’t have to turn on the light which hurts my eyes. The light betrays me, escaping under the door into the hallway. I move quietly, lifting my dresser to block my bedroom door. I lay in my bed clutching my father’s rifle. I wait for something that may never happen.

The whole world is changing and I’m not sleeping. I watch shadows move across the room as the moon drifts toward the horizon. I wonder if my lack of sleep is making me crazy. I don’t know what to believe anymore. My eyes grow heavy as the sky goes from black to gray.

III.

Something similar happened to Katarina’s family. It was her mother, at first. Then her father, whose angry words turned into angry grunts and exasperated exhales.

Neglect was the outward sign that our city was in trouble. Garbage would appear in the streets. Piles of bags and cans lined every road, waiting for a truck that wouldn’t come. Neglect appeared randomly. Packs of wild dogs began running the streets. I’d look in mailboxes and marvel at how the letters piled up. Then they would go away. Someone would drive a truck. Someone would grab the mail. Someone would find leashes for those dogs. It was like all of Perdition was trying to become normal but wasn’t sure how.

The pickup shakes as I head up the dirt drive to Katarina’s house. I’m anxious every time, uncertain what I will find. Katarina told me her parents had tried to communicate but couldn’t. She blocks her door at night like me.

Trees line the path headed to her house. Coming out from the shade of the trees only makes the darker sky more nauseating. It feels as if the entire world is turning gray. The doors are open of her father’s barn. I park on the far end of the lot in order to keep my distance. Her mother is in the barn walking around. If I let them know I am afraid, they might know I know about their ooze. I open my mouth to say hello, but my mouth goes dry. I can’t speak. Katarina walks out to me. She’s been watching, waiting for me.

We don’t talk, even in the pickup. Knowing she is fine when I see her is all I need. We know we will need a tractor. Mr. Wilson is usually good about letting us use his. Cleaning up the wreckage seems to keep us sane for a little while longer. It’s the right thing to do. Routine is a distraction we both need. She hands me a flier about a town meeting. No one will show. It’s too late. All it tells us, this nondescript flier, is that the ooze is spreading.

Katarina and I stand outside of the Wilson house holding hands. My hands tremble in hers wanting more from her than just holding her hand. I realize we haven’t really seen or interacted with people in a few days. Not like we used to. People had talked to us. Our family had talked to us. Our neighbors had talked to us. The ooze has isolated us from them. The infection has driven them deeper into themselves. How many days has it been since this began? Weeks? If only she would leave with me; we could run from this place. Doing something normal seems like the only thing that makes sense anymore.

We walk up to the house. The Wilsons don’t answer the door. She nods her head to the side, so I follow her around. The wooden fence is locked. After looking around, I find a small twig and push it through, popping open the latch. The grass is high in the backyard. We take small, cautious steps around the corner of the house. The Wilsons’ dog lies next to the door. I look at Katarina. She looks at the fence and lowers her head. I know what she is thinking. The fence to keep the dog from running away, kept it here to starve. Sagging fur stretches across visible ribs as flies buzz around its unmoving body.

I hesitate before reaching to knock on the back-sliding glass door. The morbid desire to cut the dog open comes over me. If I did, would there be ooze inside? Would the insides be coated with blackness? Katarina gasps, shaking me out of this.

When something goes missing, you don’t always notice until it is pushed into your face. As we look through the sliding glass, we see three birds clinging to the glass and tapping the window with their beaks from the inside. Katarina and I look at each other. Looking up, I see nothing flying. When had the birds first disappeared? But looking at them now, I wonder, had they really disappeared? The birds cling to the far walls like moths. My eyes draw back into the living room as the pecking from one of the birds on the door starts up again.

I don’t want to open the door. I don’t want to know what had happened to the Wilsons. I want to crawl back into bed. I feel the exhaustion consume me as reality feels out of reach. In my head, I can hear my father, pacing back and forth in the hallway mumbling or humming the one-syllabled note. The note, staggered and heavy with each exhale, sounds like he’s crying. I see him turn around, and I know I hate him. His eyes, hollow and empty, stare at me. I hate what he has become. He is weak and has allowed this thing to take over. I hate the world, the birds refusing to sing, and dogs starving to death because the owners had

“I thought winter was coming early and the fall winds pushed them south,” Katarina says. “I had no idea.”

Tap. Tap. Tap. One of the birds interrupts our conversation.

“How are they holding onto the glass?” I ask, but don’t want to look.

I close my eyes, but my mind lingers on my father’s hollow eyes. His empty expression. Opening his mouth and humming with his head bobbing up and down like a character in a puppet show.

A bird flies against the window with a thump. I shake my head back and forth as I step back. I don’t want to be here anymore. I don’t want to see the birds. I feel the breath leave my lungs as I see Katarina’s hand open the sliding glass door. I tear my hand from hers and close it to a fist. She doesn’t look at me. I don’t look at her. We stare at the birds. The bird who flew against the window hops; his head is lopsided.

“If they’re afraid, we should let them hide,” she says.

“Are they afraid?” I ask, thinking they might be infected as I stare at the bird with the lopsided head still hopping on the ground.

Katarina seems more curious than afraid. Her hand reaches towards the glass before dropping to her side. The more I look into the living room, the more I see. The birds covering the walls clinging like moths. Some perch on the ceiling fan, some on the kitchen counter. The TV reflects each small movement they make.

Before I can say anything, Katarina opens the door and rushes inside. Still holding my hand, she drags me in. I close the door behind me, holding my breath. The birds stay perched, staring at us. The smell of death is thick in the air.

The room grows darker as the birds begin to line the glass door, blocking our escape. I kick a bird that approaches me and, rather than fly back, his body caves in. The itch comes back to me, the desire to cut the dog open. I stomp on the bird. Like scratching a scab, I want to know and see the ooze come out. It still surprises me as it rises from the bird carcass toward me like an accusatory finger before falling.

We head toward the front door. The birds begin to follow in a frantic, almost blind, pattern bouncing off the walls and knocking over pictures. A trail of those who will not, or cannot, fly parades behind us with little hops. The house lets out a groan, causing me to stumble toward the wall. I see the birds staring at me. We turn into a bedroom and close the door. They start pecking at the door almost instantly. A few fluttering crashes against the door cause us both to jump.

I feel like I’m going to throw up. I lean against the door. Katarina sees it first – two bodies on the bed. One has a knife wound: Mrs. Wilson. Black ooze still pools on her body in place of blood. Her husband’s slit wrist is draped over her. The two wounds merge blood and ooze. Both have little cut marks on them from a fight. We look on curiously as the birds peck more loudly.

I want to lift the wrist of Mr. Wilson. I want to see if it is blood or ooze. I want to know who was the infected and who was not. I want to know, but in the same vein, I need to leave. Katarina is holding the door handle. I pull her away because I’m afraid she’ll let the birds in before we can decide.

I see the little hops from beneath the door. Katarina, not looking, reaches again for the handle. The bedside radio makes a groan of static, filling the room. My mouth is dry. I wonder where my cell phone is; even questioning for a moment if I ever had a cell phone. I can’t figure it out now. We have to go. We have to get away from the smell. I can’t think. I can’t process. My stomach does a somersault.

The pecking gets louder. We step back and stare at the door. I rush over to the window. I try not to look at it. I try not to memorize the streak of gore across it from whatever arterial vein was brutalized. But I know it will absorb me through the night. It doesn’t matter how tired I am. The window gives and Katarina crawls out first.

We don’t run from the house. Arms around each other like refugees narrowly escaping the disaster, we walk. Katarina closes the window after I crawl out; her compassion having run its course.

We walk around the house with a gasoline can, covering it. Katarina questions only with her eyes, but I know we are in the right. The barn has enough gasoline to douse the entire house, but we don’t need it. We draw the gasoline out into the yard, and I light it, watching the spark and flame travel as it reaches around the house in its warm embrace. Thunder booms above us and for once, I don’t pray for rain.

An Ash Wednesday service flashes through my mind. The priest’s fingers covered in oil and ash reaching for my forehead, “Ashes we came from, ashes we are going.” I reach for Katarina’s hand as the house puffs out black smoke into the sky. We wait in vain for sirens. No one comes. No Hollywood explosion. No theatrics. Just the puffing smoke of a cremation. Dread fills our hearts as we wonder at the fates of our own homes.

I turn to look at Katarina.

“Some way the world will end in fire.” She quotes one of her favorite poems.

“Some say….” I begin with the next line.

“No,” she says, “The world will end in fire.”

IV.

We don’t want to stay but have nowhere to go. We crawl into the loft of the Wilsons’ barn which doesn’t smell like animals anymore. Looking back, we should’ve talked. Our mutual silence should have spoken. It should have rung in the truth like a bell, but we didn’t want to see it. I don’t want to see it. We don’t want to accept everything is over.

The crash will stay on Blue Ridge. Doing normal things seems pointless now. The truth of the end dawning on us is inescapable. Either the crashes will pile up and replace the guard rail or there will be no one to crash on that road anymore.

Where the ooze came from, we don’t know. I wish it were as easy as saying we saw a meteor from space or some factory explosion on the edge of Perdition. Space is the easy truth. But we don’t really know. It began like a cold that broke out over summer. A coughing that turned into a fever with mucus. The mucus turned from green to black. The black mucus-soaked tissues sat in the garbage can, a visible sign that things were about to peak.

She looks at me and smiles. Seeing my expression of confusion and fear, she reaches for my hand. I feel her warmth. Instantly I feel united again. So, I tell her about the dog. It’s an irrelevant story now, after the birds. The dog was the one that showed everything to me.

“So, it was hit by a car?”

“Yes, her head turned unnaturally, barely alive. She looked at me. I saw the ooze reaching out from her matted fur. That was how I first saw it.”

She looks down before confessing, “Red Rabbit.”

She doesn’t have to say more. I have figured it out. Red Rabbit was her horse. She rode it every day. I had seen the body in the field. I had come back at night to look. Under the moonlight, where I wouldn’t be spotted, I saw the horse. It’s broken leg and the bullet hole both had ooze coming from it. The ooze had taken over the creature, making it weaker and heavier, transforming it into something else. It fell. Katarina took care of her own.

I can see her crying in my head. Leaning next to the horse, she looks up, the black ooze is coming out of her eyes. I pull my hand from hers not wanting her to see fear in my face. I don’t know what these dark fantasies are. I set my face to look at her, reassure her. Fresh tears on our cheeks, we hold each other in the glow of the Wilsons’ funeral pyre.

We stay in the barn for hours. I wonder if now she would be willing to leave. As her hand tightens over mine, I know she is telling me tomorrow. I don’t believe her. The grey clouds turn darker, and I know it is time to go. The fire is out, but the embers still fly into the air when the wind picks up.

“Tomorrow,” she says, but I break our connection by standing.

I reach down to help her to her feet.

Perdition. My thoughts bounce off the name of our small town. Tomorrow we will leave. My mind fills with sunshine and happy places – like Florida. She laughs and puts her arms around me. We walk out of the barn.

Katarina stops at a black bird lying on the ground. It still twitches with ooze coming out, its head unnaturally bent looking up at us. Katarina cries softly as I look around for a stick to poke it, reverting to childhood solutions.

“Tomorrow,” she says again.

We agree to leave at six in the morning. It’s best to avoid confrontations. I will leave at five and she will walk down the Blue Ridge Road. We will meet at the crash site. We each have little money, but it doesn’t occur to us to discuss it. It doesn’t even seem to be all that important. We know it won’t matter.

I shake my head back and forth sitting in the darkness of my room watching the shadow go back and forth under my door. My father, stuck in his pacing and rhythmic hum. Nothing is changing so we have to change in order to break this cycle.

We drive through Perdition one last time on the way home. We don’t speak. We look at the gray buildings below the gray sky. We don’t have anything to say about this place. We will leave without a word. I take her home. I fantasize about burning the town down. I fantasize about Perdition living up to its name, hearing Katarina’s voice echoing, “Some say the world will end in fire.”

My father’s pacing keeps my thoughts in rhythm. I wonder if I can reach him. I wonder if I can connect one last time even if it is just to say goodbye. My mother doesn’t pace. She is always hiding. Maybe he is fighting this. I stand and walk to my door leaning my rifle against the wall. Then hesitating, I pull a knife from my bookshelf, my favorite buck knife. I turn to survey my room wondering if I should pack something before morning; take each thing that is my favorite and put it in a bag. Take each thing that is needed for survival. Take each thing that reminds me that I am human. However, nothing holds appeal as it had before. I need nothing except Katarina. I am drunk on desire for her.

I open the door. My father stops walking, his back to me. It feels as if we’ve done this thousands of times. The cycle has to break. The hum grows more frantic. I want to speak but can’t. I let out a small groan. He turns around to look at me. His eyes look at my face, and I can see the black ooze coming out of them as if they are tears. He is gone. I know. His eyes travel down to my hunting knife.

“Da….” I begin.

He rushes toward me lifting up his arms. I step back but hit the frame of the door. His hands rest on my shoulders. I hear the humming, rhythmic in its repetitious sole syllable. The black ooze reaching out from his eyes. My head pushes against the frame of the door. I feel the knife rise and go into him. His body shudders; he stumbles back. He looks down and reaches out again. I feel the tears bleed out of my eyes, thick and wet, as the knife goes into him again.

My father falls to the ground at the same time the knife falls out of my hand. I gasp as I don’t see ooze but blood. My head cocks to the side as I approached his face to see his cheeks not stained with black but with tears. I shake him, but he is already leaving me.

“Da….” I try.

He doesn’t speak. His mouth opens and closes bobbling like a fish out of water. The hum continues but I realize looking down at him, he is crying. I push him again, trying for anything. My hand wipes his tears away. Then I see it. The hole in the middle of my palm. The black ooze alive and resting in my open palm as my entire world inverts.

I flash on the barn with Katarina and I holding hands. This is how we speak without words. I see what she sees as our ooze intermingles. We share thoughts. I flash on the ooze coming down her face in the middle of the field next her dead horse and know it wasn’t my mind trying to visualize the tragedy but her actual memory of it.

I smile at my dead father realizing my lie. Feeling like I am floating away from this hallway. We don’t speak to outsiders because we can’t speak to them. I open my mouth to speak but hear nothing. The hum was either him trying to talk or cry. Now, the veil is lifted. I look down at my father realizing this isn’t my father, and I am not his son. Not since that day on Blue Ridge when Katarina and I approached the crash of a truck we had never seen before. I flash on a memory of us collapsing near the wreckage.

I flash to visiting the Wilsons to borrow their tractor. I flash on a bird landing on me, pecking me. I see everything coming all at once. I am death. I am the bringer of the dark ooze. I have received the gift. It has already begun inhabiting the animals. Katarina and I were the first. Others will follow. More is to come.

V.

5 a.m. The sun already lights the colorless gray horizon. I remember color and how I used to love its richness. Not sleeping, I wait all night. I watch the blanket of stars vanish from one side of the sky toward the other. The clouds stretch out with the daylight. I rise and look to the field. It is time.

Everything becomes a symptom from my sleepless nights to the sky. I do not know what to believe. Aware of the ooze, I realize I am changing. I consider briefly that it may be a form of brain death. Like a hard drive, I am being erased and reformatted. Even the thunder is not coming from above but within. I had lapsed out of myself as my brain reformed itself.

I walk into the hallway outside my bedroom and make a point not to look at my father. I don’t know how I would feel looking at him, although I am no longer his son. I walk out the door of the kitchen with the screen slapping closed behind me for the last time. I walk past the truck; I decide to walk through the field to Blue Ridge and find Katarina.

I walk through the small patch of open woods and replay the week. I don’t feel guilt. I should. I should feel something. But all I feel is love for Katarina. Intoxicated with her, I need to see her.

The trees are cold. I realize briefly that it is cold outside. When I exit the woods, I see what looks like a slow drop of rain fly past me. It is now snowing. I can see Katarina waiting for me. She walks through the remnants of the devastated moving truck. The snow flurries lift her hair. The sky goes from gray to white.

I see multiple wrecks alongside the moving truck. With no ramp, this area collects debris and devastation. I approach Katarina from behind. My hand reaches out and joins hers. I can feel the ooze coming as it merges with hers. I know now we speak through the ooze. As she looks at me, her eyes grow wide, knowing. She smiles, reaching her other hand out to caress my face before kissing me. She has known. I thought I had been waiting for her, but she had been waiting for me.

“What do we do now?” she asks. “Do we stay? Do we go?”

“Go” is the only thing that comes out of me.

We don’t leave right away. We look at the wreckage, considering how everything is changing, I wonder if others have been infected yet. Katarina smiles at me. Her black hair, white specks of snow on it. Hadn’t her hair been brown before?

“Trial and error” she reflects as we glimpse on our memories of the Wilsons. The screams, the panic as they fight back, and then the birds swarm them.

We glimpse further back. We see the first trailer tumble and break. We feel the ooze reach out and touch us. We feel the echoes of timeless galaxies. Tribes more and less sophisticated, nomadic and sedentary, hungry and full-grown together in the ooze, reminding us of Earth’s next step in evolution. A million suns rising and setting like ours.

Another screech of tires cries out above us. Dumbfounded, we look to see a pickup heading over the edge. The truck’s first lunge against the embedded rocks shatters part of the glass as it tumbles and breaks apart. After making a 360; the rear shatters, shooting out shrapnel. We cannot move fast enough as torn metal flies at us.

Katarina’s body writhes in a death shiver as she turns her head to look at me. I try not to look at her body. I try not to see the pieces of her crushed and broken and beautiful body. I try to cough but realize I can’t breathe. I wiggle my fingers, trying to move my hand.

Katarina’s eyes break from mine to look at my body. Our hands still holding, I see part of the axel sticking through my torso. I feel dizzy as the world spins around me. We marvel at each other’s ruined vessels. Disbelief clouding our white sky.

“Some say in ice.” She smiles reassuring me as her life fades. I feel her seep from my consciousness. I want to cry. I want to scream. I want to do anything. But my body is as broken as hers.

I tighten my grip on her hand, but she is gone. The cold makes me shiver. I feel the restraint of my physical body cry out against its limitations. Knowing now, I am alone, and I have no more reason to keep going.

“Some say the world will end in fire,” she had quoted, “Some say in ice.” I can’t remember the words except for the last lines. The last lines take longer to come. Long enough to make me think I would die before I remember. Then the spark of memory, “To say that for destruction ice is also great and would suffice.”

Suggested Reading

-

about Lollipop, Lollipop![Lollipop]()

Featured • Fiction • Nonfiction

Lollipop, Lollipop

The figure moved slowly, deliberately, its shrouded head turning towards Josh. Those eyes—sharp and frigid as icepicks—stared at him. The man’s black lips never moved, even as a word pierced him like a yell: “Beware.”

Featured • Fiction • Nonfiction

-

Featured • Fiction

-

Fiction