Engagement

It was 8:00 a.m. on Lake Sue, and Minnie was kayaking—the only human on the lake except for a stoop-shouldered, gray-haired man fishing for bass in a silver skiff. Minnie could feel the awakening Florida sun on her shoulders and thighs as she glided through the inky blue water. Except for some faint lawnmowing in the distance, it was a peaceful, placid morning. She reached and pulled, reached and pulled. She tried to ignore the hollow feeling in her gut. She tried focusing instead on the sound of rippling water, the frogs, and the occasional loon. She heard a small splash to her left, probably a fish. Even that reminded her of last night’s fight.

Minnie and Greg had been engaged for one year. They were high school sweethearts who had remained together through University of Florida, where Minnie had rowed crew and been a B- student, and Greg had played water polo and gotten straight A’s. Greg was Minnie’s first kiss. Minnie was the person who got Greg through the death of his father two years ago. Greg’s was the shoulder Minnie cried on when her older sister, Meredith, entered rehab for cocaine addiction mere months after Greg’s father’s death. When Greg proposed to Minnie on a sailboat in Kauai one year ago, everything had been perfect: the suddenly appearing rainbow, the dry French champagne, Greg’s scripted words. Minnie had just landed her dream teaching job at her hometown high school, and Greg had just finished Wharton Business School. It appeared as if everything was falling into place.

Though she kayaked four times a week, Minnie wasn’t scheduled to go out this morning. She was supposed to meet her mother, Bitsy, for brunch at the Imperial Club to pick out bridesmaid dresses. But the argument last night had changed the morning plans—Minnie had drunk too much red wine and tossed and turned until dawn. She awoke with a need for fresh air and convinced her mother to reschedule for later in the day. Bitsy, a diminutive, Southern woman who still believed a woman’s value came largely through her physical appearance, and was confirmed by marriage, mistakenly thought Minnie was trying to lose weight for the big day: “Oh, good for you, sweetheart. I’ve always said you have to overcorrect for your athletic build. How about an early dinner instead?”

Minnie reached and pulled, reached and pulled, and finally surrendered to the details of last night’s argument. She heard a larger splash and turned her head sharply to the left, wincing at the glare from the diamond in her ring. Initially, she’d felt proud when her mother and girlfriends had groaned in ecstasy at the viewing of her ring, but on days like today, she found it cumbersome, and almost ridiculous. Minnie stopped paddling and placed her blade inside the boat. She removed the square-cut ring and slipped it into the back pocket of her black running shorts. Something bumped into her kayak.

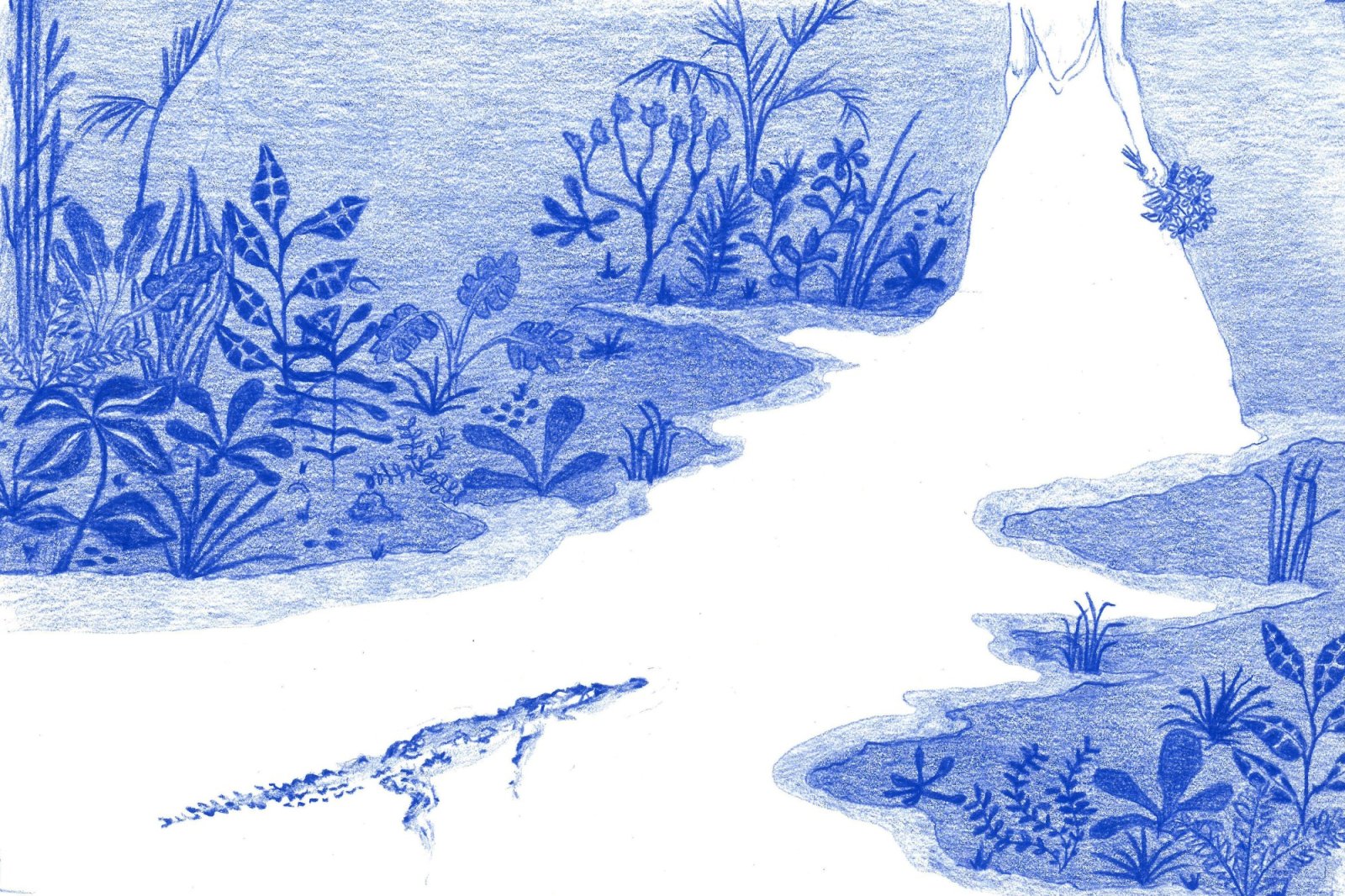

Raising her head, expecting to see a piece of wood or a dead fish, she spied two prehistoric eyes staring at her. About five feet in front of her, at the bow of her fiberglass boat, rested an alligator head. Minnie sucked in her breath and froze. The gator’s almond-shaped eyes, unblinking and incurious, stared at her. Its pupils were vertical, not horizontal, the shape not unlike that of a narrow diamond. Minnie was mesmerized.

The boat continued drifting, and Minnie’s heart skipped. She felt a throbbing in her ears—her heartbeat; the creature’s head was now about four feet to her right.

She retrieved her paddle with as little movement as possible, freeze tag-like. And, slowly, as through maple syrup, she backpaddled away from the gator. It did not move.

Once she was ten feet away, Minnie exhaled and relaxed her shoulders. The wind shifted, ushering in a smell of rotting vegetation. Still paddling backwards, she looked around to orient herself and realized she’d inadvertently traveled in the direction of Haliburton Canal, a favorite breeding spot for Sue gators. This mistake surprised her.

Minnie turned her gaze back to the creature, which was now roughly fifteen feet away. They stared at each other a few seconds more. Could this animal smell fear? The gator’s head ascended above the surface several more inches. Minnie’s heart began to race. She recalled her old lifeguard training about how to fend off an alligator attack. If an alligator attached itself to a person’s limb, it would likely try to roll the victim. The victim was supposed to allow the roll, without becoming disoriented. Poking the gator in the eye or punching it in the face were recommended. Good Lord, she hoped it didn’t come to that. She paddled backwards some more, making space, hoping the gator would not notice, but its mossy, knobby skull and snout were now fully above the water. A heron whooped overhead. Then, suddenly, the gator closed its eyes and disappeared beneath the surface.

Minnie exhaled. Her heart was thumping, and her palms were slippery. She was now twenty feet away from where the alligator had been. She stopped paddling, turned her kayak around, and headed towards the center of the lake. She picked up the pace and rowed aggressively in a wide arc around where the gator had submerged, then towards home. Remarkably, her eye, which been spasming on and off—almost daily—since Greg’s proposal, stopped twitching. Her breathing returned to normal. She scanned the lake and noticed that the water was bluer, and the cypress trees greener. The scent of orange blossoms was heavy in the air even though she was in the center of the lake. In fact, everything—including her—seemed more alive.

She’d not seen the gator’s body, but the distance from its eye-ridge to its nostrils was about eight to ten inches, which meant the body length was close to ten feet. She began to laugh as she got closer to home. She, Minnie Sayre, middle child of Gabriel and Bitsy, and future wife of Greg Alsinbrook, had stared down a Florida gator. She felt euphoric, like she used to feel after triumphant crew races. Smiling, she reached and pulled, reached and pulled, and felt the warm swish of her ponytail against her back, tickling her delicately, like a feather. After a few minutes, the house she and Greg owned together, a quaint Florida bungalow her parents had helped get for them, came into focus. Her paddling slowed; her stomach tightened. She turned back toward the middle of the lake and scanned the surface. Nothing. Only the ripples glistening in the light. Then she paddled the kayak up onto the sandy shore of her backyard. She sat there with her eyes closed for a few minutes, then forced herself to pull up her knees, grab the cockpit rim with her hands, and lift herself out of the kayak.

Last night, she and Greg had fought about the wedding venue over shish kebabs, kale salad, and wine. They’d been eating outside on the back porch, watching the pinks and oranges bleed out into dusk. This fight was like all the other fights they’d had since getting engaged: it started calm and ended with a happy and victorious Greg and a confused and deflated Minnie.

“Min, your parents want the big church. I want the big church. We will have close to three hundred guests… The big church makes sense.”

While he was expounding, she looked out at the lake and counted coots to calm herself. There were twelve. Greg had always been more intellectual, and a better debater than she was. She sometimes wondered if she’d have to attend law school just to beat him in a fight.

“I don’t want a big wedding in a church, Greg.”

“Why not? Give me three reasons.”

Now she counted fifteen coots. Three had joined the group. She was already feeling exhausted from this discussion. She wanted to finish the bottle of wine, go for a run, go for a swim. She’d end up an alcoholic or an exercise bulimic by their wedding day.

“Greg, I’m tired, and I’m pretty sure I’ve given you three reasons before. Why does every argument with you have to be like a courtroom scene from a John Grisham movie?”

“Min, darlin’, this wedding is not just about you.” He put his kebab down and took her hand. “Come on, we’ve both had a rough few years. My dad… Meredith. Wouldn’t it be nice to have a big party for everyone to be happy at?” His voice got soft, pleading. He’d always had a magnificent voice. The first time she met Greg, sophomore year in high school, she heard him rather than saw him. He was teasing Wade Castinetta at the lockers, and Minnie walked by and heard a deep, velvety southern voice proclaim, “Dude, the AP Bio test was in-tee-ents today.” Something about the way he turned intense into a three-syllable word along with his James Earl Jones tenor made Minnie turn and stare. Also, AP Bio was her favorite class.

Minnie was not beautiful, but she was wholesome-looking and pretty—and six feet tall. She had broad shoulders and a lean build, long brown hair with caramel streaks, and skin bronzed from her days on the lake. Her face was oval-shaped and plain, except for her eyes, which were a deep, almost navy blue. They were large and slightly bulging, which made her look surprised rather than unwell. As a child, classmates had teased her and called her “Olive Oyl,” but once Minnie grew into her expansive eyes, the teasing stopped.

Greg loved her height (he was 6’3”), and on their first date, he’d confessed that he was attracted to her quietness and athleticism. Minnie had melted. Most boys ignored her, and she didn’t know why. Her father told her they were intimidated by her. Her mother told her she needed to wear shorter skirts and giggle at jokes more. Minnie and Greg were dating by junior prom, and had been together (except for a few, small breaks after big fights) ever since.

But arguments like this one made Minnie feel like her brain had been tossed into a blender turned up to maximum speed. If Greg was right, she was being selfish, and she owed it to him and their grieving families to have a large, festive, church wedding. But she thought the wedding should, at least partially, resemble what she wanted. And she’d told him she wanted an intimate affair on a beach somewhere, perhaps in their own backyard or at Avon Beach, where she and Greg had spent many a high school weekend. She’d told him she wanted close friends and family only. Then, if Meredith—whom Greg and her mother were afraid to even invite to the big wedding—if Meredith behaved poorly, it wouldn’t turn into a town scandal. She’d asked him: “If a bride hates her wedding, doesn’t that bode poorly for the marriage?”

But he hadn’t seemed to hear her. And now as she listened to more data-filled remarks, she felt the life seeping out of her. She didn’t have the stomach for conflict.

“Okay,” she said. “Okay. Okay. Okay.”

Greg stood up and raised his arms in mock victory, then bent down and kissed her on top of the head, and went inside, smiling. Minnie remained outside, relieved but unsettled, and finished the bottle of red wine. Twenty minutes later, with her eye twitching uncontrollably, she climbed into bed where Greg was hoping for sex. She said, “Sorry, I’m tired,” and turned off the light.

This morning’s paddle had cleared her head and put things into perspective. Worrying about wedding plans seemed petty when looking into the eyes of a ten-foot alligator in the middle of a lake. Plus, Minnie always felt most herself when she was alone. She could think without others trying to influence her. Everything was framed more realistically, like the natural world and physical exertion reminded her how to be human, how to be herself. For the first time since her engagement, she allowed the thought to enter her head that she could call off the wedding. In fact, she vowed to herself that if the planning did not become less contentious, she might. Life was short.

Minnie hauled the boat up on the sandy beach of the backyard. The one-story, shingled house was gray with corn blue shutters. She could see the ceiling fans in the family room and master bedroom whirring from where she stood. She heard Tim McGraw on the radio inside and smelled bacon frying. She loved this 1920’s bungalow. It reminded her of photos from Old Florida, back when there were more wild birds and reptiles than Northerners (or “carpetbaggers,” according to her father).

She walked into the kitchen and found Greg standing at the stove, his muscled back to her, preparing breakfast. His left foot was resting on his right calf, flamingo-like. He was dressed in crisp white shorts and a white polo shirt. He almost looked like he was posing for Architectural Digest. She went to the refrigerator for orange juice.

“How was the lake?” he asked without turning to her.

“Fine… glassy,” she responded.

“You want some breakfast?”

She hesitated and responded, “Sure,” even though she wasn’t hungry. She knew he’d complain if she didn’t eat, and she didn’t want the spell to be broken just yet.

Greg turned around and handed her a plate of bacon and scrambled eggs with chives. He watched her while she took it, then turned back towards the stove. Tim McGraw belted out, “I like it, I love it, I want some more of it,” in the background. Minnie envisioned the alligator descending into the water as she picked up her fork. She felt nauseous.

“You know—I’m actually not that hungry,” she said, returning her fork to her plate.

He turned around to face her. “C’mon, how about just a taste? I went to so much trouble.” His voice was tight.

She looked down at her plate and felt like a child. Greg was staring at her, willing her to eat the gourmet breakfast he had just prepared. In the past few weeks, Minnie had started to sense she was living two lives: the life she acted out for others to see, and the life inside her head. For example, right now, inside her head, she was telling Greg to fuck off and shove his chivey eggs and Tim McGraw up his ass. But outwardly, what she did was scoop a tiny bit of egg onto her fork and raise it towards her parched mouth. Greg walked around the island and sat down next to her. He used his feet to turn her stool toward him. The eggs fell into Minnie’s lap; her fork clattered loudly on the hardwood floor.

“What’s wrong?”

Minnie stared at the fork and willed herself to be truthful. She took a deep breath, “What’s wrong is that I don’t want breakfast.” Her voice was shaking.

Greg reached his hand over her shoulder and tugged her ponytail. He was breathing calmly, trying to regulate his own breaths to regain equanimity. Minnie’s face got hot. “Let go,” she said. He did.

“Fine, Min, don’t eat. I’ll feed the leftovers to the gators.”

He got up from his seat, retrieved her plate, and returned to the sink. Minnie sat there, frozen, processing his words. Greg turned on the water and began to wash dishes. Again, he performed the flamingo with his legs, and hummed, “I like it, I love it…” She imagined him falling over to the right and landing on his elbow on the hard floor, sudsy water from the skillet seeping into his white clothing. The phantom cracking of his elbow made her laugh.

Greg whipped around, “What’s so funny?” His light blue eyes were blazing. Meredith used to joke that Minnie and Greg would create children with eyes all shades of blue. She also said that blue was the most common eye color of narcissists. Her older sister’s vast knowledge of random facts had always impressed Minnie.

Minnie cleared her throat and sat up straighter on the stool. “Greg, we need to talk about all this wedding stuff.”

His face froze and then softened, like a snowman’s right before the melting. “I’m way ahead of you.” Cheeriness returned, Greg continued, “I thought we’d go pick out invitations this afternoon.”

“Invitations?” Minnie’s brain began to buzz. She had just been in control two seconds ago. Now she felt like a tiny bird flapping its wings in the wind, suddenly unable to fly.

Certainly Stationery was a 100-year-old family-run store on Park Lane’s version of Main Street. Inside, it smelled of gardenias and crisp paper; the door tinkled when Minnie and Greg entered the premises later that afternoon. The owner, Mr. Ponder, was a proper and gentle grandfatherly type. Minnie’s sister had worked there two years ago after dropping out of college. One sunny Saturday morning, Meredith had shown up to work so high from the night before that her nose was bleeding, and rather than scolding her, Mrs. Ponder had taken her into the back room to give her Kleenex and coffee. She then called Bitsy and asked her to come retrieve her daughter.

Days after the incident, on the drive home from school one afternoon, Minnie gathered up the courage to ask her mother what had happened. Bitsy squeezed the steering wheel so tightly that her fingers became bones. She replied, “Your sister got a terrible nosebleed all over Mr. Ponder’s luxury cream card stock.” She forced a smile and turned to face Minnie, “It was quite a mess.”

“Ah, hello there, you two.” Mr. Ponder, in a white, short-sleeved, dress shirt and navy-blue bowtie, walked out from behind the cash register to greet them. Silver spectacles rested on his nose. He smelled like aftershave and mothballs. He shook Greg’s hand, then patted Minnie on the left shoulder. “I was wondering when you’d pay me a visit.” He winked.

Minnie’s eye popped and seized. She reached up to rub it and make it stop; Mr. Ponder led them over to a table in the back corner of the store. Five black notebooks, overflowing with colorful card stock and cream and white invitations, awaited them atop the table.

“The whole town is excited about this wedding,” Mr. Ponder said softly.

Greg and Minnie sat down at the table. Greg took a notebook off the stack and began to turn the pages, examining the various shades of white and cream invitations. An image of blood smears on virginal, white cards appeared in Minnie’s mind. What were they going to tell Meredith about the wedding? Certainly, she would hear about it. Even Mr. Ponder, the purveyor of Certainly Stationery, already knew.

“Min, look! This is perfect.” Greg stared at a large cream-colored invitation with heavy, black print. Dainty and tasteful gold hearts were scattered around the edges. It was romantic, Victorian-chic. He leaned down closer to the invitation. The tips of his ears were pink. His excitement was electric. When they’d first started dating, Greg’s ears would turn pink before he leaned in to kiss Minnie. His nervous ardor was captivating. Minnie felt like the luckiest girl in the world to have a boyfriend whose ears blushed before a kiss.

Greg pushed the heavy notebook towards her. It smelled like plastic, fresh card stock, and order. She looked up at Mr. Ponder, standing off to her left, who was nodding his head up and down and clearing his throat, anxious for her to like something. She looked over to the right and saw a weeping willow swaying in the late afternoon sun outside a window. Three midnight blue songbirds were perched on the willow branches, clucking and pecking.

The invitation was lovely, not her style—those hearts were a bit much—but lovely. Her mother would approve. Greg loved it. Choosing this invitation was an appealing path of least resistance.

This morning, her emotions had traveled from peaceful and elated to chastised and enraged. Now she was in a lovely stationery store, with kind Mr. Ponder, an expectant fiancé, and disturbing memories.

She bent over the creamy, romantic invitation, feigning scrutiny, and looked up at Greg, then Mr. Ponder. “I love it.”

“You do?” Greg was doubtful.

She turned towards Greg and put her hand on his. She nodded her head up and down and smiled. “It’s really pretty.”

“But, I mean, this is the first one we’ve looked at.” He looked up at Mr. Ponder, “Does that ever happen?”

Mr. Ponder cleared his throat, “Well, not often, but that’s a beautiful invitation, and we just got those in.”

“I really don’t need to see anymore.” Minnie tried to insist.

“Why don’t you look through another book before you decide? I think you might like these as well.” Mr. Ponder handed Minnie a second heavy black book.

“Min, please. I’d feel better if you looked at more.”

She rolled her eyes and exhaled, “Fine,” and took the book from Mr. Ponder. She thumbed through it, trying to look engaged, scanning the names of the couples: Nina and Tom, Jeannie and Jack, Ben and Mary Blake. Greg looked on and clucked approval at a few. After a few pages, Minnie lost interest and turned the pages robotically. She put the book down and turned to Greg, “I really like the first one.”

Greg narrowed his eyes, “Do you really like that invitation, or do you just want this to be over?”

Mr. Ponder sighed and excused himself to go help another customer. Minnie was on the verge of responding, “Both,” when her phone rang. It was her mother.

“How is invitation shopping going?”

“Um.”

“Listen, can you meet me at the club earlier? Something’s come up for later tonight—a party I completely forgot about.”

Minnie did not want to meet her mother earlier. But she didn’t want to be at Certainly Stationery right now either.

Minnie walked into the Imperial Club. The inside of the dining room smelled like faint mildew and roasting meat. She noticed paint chipping off the white Italian-style column in the far corner of the dining room. As a child, this place had been magical—chocolate chip pancake brunches on Saturdays, Easter egg hunts on the back lawn, the occasional illegal cocktail from the back bar when she was home visiting from college. Now, it looked sad, dated, and droopy, like a Roman restaurant desecrated by an onslaught of cruise ship passengers.

Bitsy was already seated at a table in the center of the room. Her right hand was perched atop a stack of wedding magazines, and her long red nails were impatiently tapping the cover of Southern Bride, the spring 2000 edition. She was dressed in a hot pink and yellow silk dress, patterned in hibiscus flowers; her feet were adorned in pink, rhinestone sandals. She had enormous, circular, Chanel sunglasses on—inside—and Minnie wondered if she was trying to look like a celebrity.

Bitsy looked up and frowned at Minnie’s white blouse and denim skirt, “Why don’t you ever wear that cute little red number I gave you? It’s so flattering.”

Minnie sat down. She picked up her mother’s chardonnay and took a gulp. “Mom, I’m not comfortable in clothes like that. Also, I’m a teacher… remember?”

“Well, you’re not at school.”

Minnie took another sip, “Yes, but I could see my students out.”

Bitsy took off her sunglasses and stared at her daughter as if she was a stranger, “I have never understood your disregard for appearances, dear. You must have gotten that from your father.”

Minnie smiled. Her father, Gabriel, was a third-generation Floridian who loved to fish and hunt. He wore suits to work (he was also a third-generation defense attorney), but shorts and brown, leather flip-flops everywhere else. Many in town could not understand how he and Bitsy were still married.

Margarita, their server, arrived to take their order.

“What would you ladies like today?” Margarita was dressed in black slacks and an orange blouse. She was petite, with large breasts, and wore her black hair in a bun. She was a grandmother but didn’t look a day over forty.

“Please bring me the chef salad, no dressing, or onions, with an avocado. And another chardonnay… And Marguerite”—Bitsy always said her name wrong—”do not bring me that house wine again. I had a terrible headache from that last time.” She looked into Margarita’s eyes sternly, as if speaking to a child.

“I’ll have the burger and a glass of red wine, thank you.” Minnie closed her menu, took her mother’s, and handed them both to Margarita. They smiled at each other over the menus. They liked each other. They had a shared embarrassment of Bitsy, who was ever a difficult customer.

As Margarita walked away, Bitsy said, “My, she could use more deodorant.”

Minnie felt a headache looming; her eye twitched. “Mom, what do we need to decide today?”

“Well, I’d like us to pick out your bridesmaid dresses and discuss the wedding party.”

Minnie leaned back and rubbed her eye. Bitsy looked around the dining room to see who was in attendance. She smiled at the Rileys, a local family who was there with their daughter, Sally, who was the same age as Minnie. To Minnie’s horror, Bitsy picked up the next wedding magazine in the stack, Weddiculous, and waved it in the air, as if to say, “Look at what we’re doing today!” The Rileys smiled politely. Minnie knew that her mother felt triumphant, as if marrying off one’s daughter was a race. Sally was pale and nervous and, as far as Minnie knew, had never had a boyfriend.

“Mom.”

“Yes?”

“Can you focus, please?”

Bitsy turned her attention back to her daughter. “I’m just saying hi to the Rileys.” She took another sip of wine. “And don’t roll your eyes at me, young lady.”

Minnie’s heart rate spiked. She began to sweat. “Mom, I’m not sure…”

Bitsy looked up, perturbed. “You’re not sure of what?”

“I’m not sure I’m really in the mood for this today.”

“Oh, don’t be ridiculous. You’ll be fine after your wine. Now,” Bitsy peered forcefully into Minnie’s eyes. “The biggest thing to decide today is what to do with your sister. I’m not sure she can be at the wedding, what with her…”

Minnie’s eye almost lunged out of its socket. She knew what was coming next. This was a topic Greg had brought up with her as well. Neither Greg nor her mother wanted Meredith at the wedding. They feared she’d do something to embarrass the family. Minnie thought a three-hundred-person wedding without her sister would break Meredith’s already fragile heart, and Minnie wanted no part of that.

Margarita arrived with their drinks and bread and set them down. She glanced at the wedding magazines and then back at Minnie and smiled grimly. Minnie picked up her cabernet and began to sip. She raced through her mind and considered what to say next. Nothing would work with her mother. It was just like arguing with Greg. It all led to blender brain. But Minnie forged ahead, more out of habit than from confidence.

“Mom, we cannot not invite Meredith,” she said.

A sigh, then silence from Bitsy.

Minnie continued, “I mean, she’s my sister for God’s sake.”

More sighs from Bitsy, a bit of sunglass fidgeting. A few sips of wine, then a sunglass donning. Bitsy looked directly at her daughter, through her sunglasses; an expensive, musky Moroccan perfume emanated from her direction. Laying her hand atop Minnie’s, she lowered her voice and spoke softly, “Wilhelmina, I know you love her. She was very good to you as a child, but…” Minnie tried to find her mother’s eyeballs through the ridiculous sunglasses, but she could not. Bitsy leaned in closer, “She could literally ruin this wedding.” Bitsy turned her head to the right and looked out the window. She inhaled deeply and leaned back in her chair, hands clutching the edge of the table. They were trembling, “I’m just not sure I could take that right now.”

Her mother’s trembling hands, and the reminder of Meredith’s sisterly love, caused some type of shift within Minnie, a softening. The statue that was her mother was showing the tiniest crack. Could it be that fear or a lack of confidence drove Bitsy as much as her selfishness and superficiality? This thought had never occurred to Minnie before.

Minnie looked down at the table and back up at her mother. She saw her own reflection in her mother’s sunglasses—her Olive Oyl eyes, the thick eyebrows she shared with her sister, her slightly sunburned nose. Her mother cocked her head to the right. Her perfectly lined pink lips twitched. Minnie leaned forward and said, firmly and slowly, “I’m not having a wedding without Meredith, Mom. It... wouldn’t be right.”

Her mother’s shoulders hunched forward. She removed the giant sunglasses and wiped her nose. It was as if Minnie’s exhaustion had jumped across the table and entered Bitsy’s petite body. “Greg will not approve,” her mother whispered.

Minnie exhaled, feeling lighter, “I really don’t care.”

Margarita arrived with their food. Minnie ate her burger enthusiastically. Her mother seemed distracted, picking at her salad and looking around the dining room to surveil who was in attendance.

A well-dressed family of four walked into the club. Bitsy sat up straighter in her chair, slightly recovered, and followed the family with her eyes until they were seated. Minnie could tell she was assessing their wealth and trying to figure out who they were. Bitsy turned back towards Minnie and leaned forward, whispering, “I wonder if that’s that new family from California? Everyone’s talking about them.” She then proceeded to pick up Southern Bride from the magazine stack on the table and fan herself with it, hopeful eyes darting around the room.

Minnie swallowed a piece of burger and told herself to be nice. Her mother’s heart, like her own, had been fractured by Meredith’s suffering. She thought of something her mother would like. She leaned forward and whispered, “The California mother’s skirt is hideous.”

Bitsy stopped fanning and turned towards Minnie. She smiled the free and unselfconscious smile of a child. Then she stabbed a large piece of romaine lettuce and boiled egg with her fork and finished her salad.

Minnie walked the two miles home from the club to process the day’s events. She and her mother had decided on a few bridesmaid dress options at lunch, and they agreed to shelve the exact wedding party number for another date. Minnie was feeling stronger, a bit more in control; she was almost happy.

She passed by the homes of people she’d known all her life: the two-story Italian-style home of the Watsons, whose son had gotten brain damage in a high school lacrosse game ten years ago; the red-brick colonial of the Samilas, who had no children but five cats that wore sweaters whenever the temperature dropped to 75 degrees; the blue Nantucket farmhouse owned by the Farbers, whose daughter was represented by her father after a DUI in high school. She wondered what a casual walker would say about her parents’ gray Victorian two streets over. That’s the house where Meredith Sayre snorted all her God-given talent up her nose and had to be institutionalized. That’s the house where the mother became desperate for control and the jovial father became scarce. That’s the house where Greg Alsinbrook’s fiancée grew up. As a child, Minnie had loved knowing the stories of these neighbors. It made her feel included and important. Today, it made her feel old and amused, as if she were a long way away, as if she’d outgrown them all.

When she got home, Greg was gone. A yellow Post-it note was taped to the refrigerator. It read, “See you tonight. Need to finalize invitations!” Her mood plummeted; her eye twitched. Usually, she was happier and more relaxed when she was alone. But increasingly, even the trace of him, the stupid little sticky note, made her feel confusion and doubt. She stared at the note, and her eye twitched again, absurdly.

Minnie knew she didn’t have this invitation conversation in her. She’d just managed to survive a meal with her mother, and though buoyed by potential triumph over Bitsy with the Meredith invitation, she’d have to repeat this process with Greg. Then, she’d have to look at more invitation tomes and pretend to be amazed. And what was next? And next? A lifetime of these moments of dread descended on her like a lead weight.

She removed the note from the door and held it in her left hand. She pressed her face and body into the cool, stainless-steel surface and inhaled the metal. She raised her hands over the refrigerator door until they were resting on top of it, fingering the dormant dust. After a few seconds, she took her hands off the refrigerator and stared at the dust on her fingers. She twisted her engagement ring and removed it to see what her hand looked like without it. It looked more natural, more itself. She slid the ring back on and stared at it.

Minnie opened the refrigerator and poured herself a glass of water. She guzzled it and then began to hiccup as she walked outside to the backyard. She dropped down onto the moist sand of the shoreline, removed her white sneakers, and dipped her toes into the water. She hiccupped again. The sun was beginning to set. Soon there would be cantaloupe oranges, watermelon pinks and maybe a tomato red. She took a large sip of water and a large gulp of air and leaned back onto the sand.

A creeping, cathartic tiredness seeped into her skin. She leaned back on her elbows and turned her face to the darkening sky. The tips of her hair touched the sand, and she waved her head back and forth, letting it tickle her shoulders. She closed her eyes and listened to the beeping and crackling of the cicadas and frogs—a symphony of miniature car horns. Her elbows sunk into the sand; she pointed her toes and stretched her feet further into the water. The gentle lake waves lapped her ankles, like a dog asking to play.

After a few minutes, she felt an uncomfortable squeeze, and then a tug on her large right toe. It surprised her, and she tried to pull her leg back towards her torso, but it wouldn’t move. She opened her eyes and sat up. There was an alligator head attached to her foot. It was almost dark, but Minnie could see that its eyes were closed, as if concentrating. Its long, dinosaur-like tail lifted slowly in the water behind it, and came down with a splash. A buzzing sensation, like swarming wasps, filled Minnie’s brain. Her toe hurt, and she tried to wrench her leg back, more strongly this time. She felt a burning sensation in the knuckle of her toe, and then near her ankle. Now her whole foot was in its mouth. The gator’s tail thrashed again, and she felt the jerk on her leg, and her bottom moved along the sand toward the water. It was pulling her into the water. Its tail thrashed again, louder, and she felt herself pulled all the way down the sand and under. Her ankle seemed to crack; a shot of pain raced up her leg. Water burned her nose, and she could no longer breathe. She opened her eyes and looked up to the surface. Three stars, the first stars of the night, shone down on her through the rippling water. The gator flailed, yanked her leg, and pulled her deeper. The surface grew choppy. She reminded herself to allow the roll. Let the creature roll you. Then, when it’s confident it has you in its grip, fight back. She could do that, she told herself. Yes, now, she could do that.

Suggested Reading

-

about Lollipop, Lollipop![Lollipop]()

Featured • Fiction • Nonfiction

Lollipop, Lollipop

The figure moved slowly, deliberately, its shrouded head turning towards Josh. Those eyes—sharp and frigid as icepicks—stared at him. The man’s black lips never moved, even as a word pierced him like a yell: “Beware.”

Featured • Fiction • Nonfiction

-

Featured • Fiction

-

Fiction