The Girl in the Pink Dress

You were dreaming the night you found her again in the haunted house where the lost girls live. Sitting in a barren room off the stage-lit hallway lined with too many doors. Conversing with a boy you dated in high school who once talked nonstop about Steve McQueen, the movie Vanishing Point, had clearly practiced that demi smile in the mirror.

He was your age now in the dream, the Steve McQueen wannabe, head bowed, telling you how much you had meant to him in the muffled murmurs of a penitent in a Confessional. You nod the way you often still do in lieu of speaking your mind, in a way that conveys agreement but translates to “are you fucking kidding me?” in the ancient language of your planet.

And then you are opening a door to another room where the lost girls live to find the girl in the pink dress. A crumbling of galaxies inside you. Not a dream of her, you understand, but her, your daughter, at two years old. Your friends Peggy and Beth came from Oakland bearing the world’s largest and perhaps only chocolate duck from that shop on Union Street—remember? That’s right, a duck; in an edible Easter Bonnet.

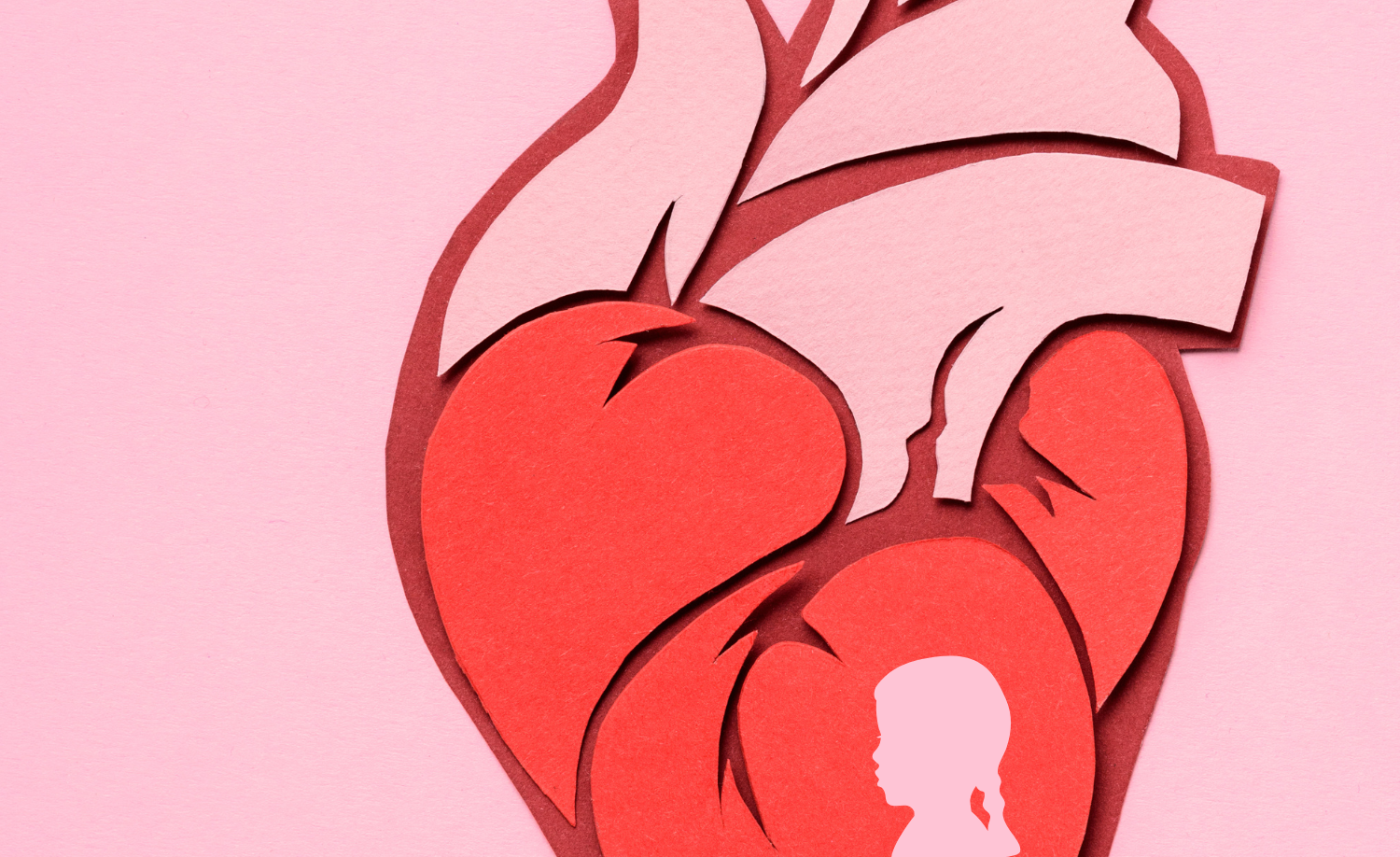

Save for a blurred figure you take to be a daycare worker, she is alone, your daughter, her eyes on fire at the sight of you. At three months old, she once rolled all the way across the carpet just to reach you. She is holding a stuffed rabbit by one long ear, cheeks flushed, that pink, empire-waisted dress with the white lace collar your mother sent, a hand-crocheted sweater from your friend Rebecca. Her nose is running.

How could you have left her?

You are holding your breath as you lift her. She drops the rabbit, runs her small hands up and down the outside of your arms. Not a dream child, you understand, but your actual daughter at two years old—all of you.

You wake still holding her pressed to your chest for endless seconds. And then you are choking, sinking, drowning; having lost her all over again.

__________

“Just remember, everyone in your dream is you,” says your therapist friend, whom you adore.

You nod, a little too vehemently, to disguise the dissent kicking up in your solar plexus that leaves you gripping the sleeve of your cardboard cup. Exerting the kind of pressure that might have caused a stronger woman to cinch the cup’s waist, blow its plastic lid.

But you are no longer a strong woman.

The music emanating from invisible speakers—mournful, acoustic ballads you think you know and then realize you don’t—pleadings of another generation.

A spoon clinks against the metal coffee counter. You flinch.

Your friend means well and is right, of course, about the content of dreams. But not about the girl in the pink dress.

She was not a figure in your dream or a wounded child part of your psyche. She is your two-year-old daughter, the scent of baby shampoo and Peeps. She has a cold and you need to take care of her and you are swaying on your feet to the lullaby of that possibility presented once again—Autumn to May.

Her hands on the wings of your shoulders move in circles and when you wake up rubbing your arms and singing you are willing to trade whatever time you have left.

The coffee shop proprietors have switched out the last art show for a new one. Wood cuts of post-apocalyptic trolls have replaced linoleum prints of whimsical space travelers, now returned to the mother ship. You bought your daughter one of the latter for her 30th birthday last week. A bubble-headed stick figure with outstretched arms, teal rectangle of a body, smear of rust suggesting a horizon you could count on for navigation.

Your friend is still talking about dreams and their inhabitants. You love her and she means well and is right about almost everything most of the time. But she is wrong about the girl in the pink dress.

__________

Last night, you dreamt you were at some kind of coastal resort in that place where it is always twilight, being driven at terrifying speeds in a pink, toy-like convertible by a couple of teenage girls who can’t see you to a strand of shops jutting into the bottomless sea of a foreign land.

You walk into a coffee shop completely open to the street, where a man you had befriended earlier in the dream stands at a round table in the back, sipping espresso. You secretly hoped he would be here, didn’t you, that you could finally speak with him alone, indulge your attraction?

He waves and you join him, begin chatting, interrupted almost immediately by commotion in the street. You see him before your companion does. Active shooter—the video in the employee training program on instant replay, and pull your companion to the ground. Fellow shop patrons are screaming, dropping, the cinematic pop, pop, pop.

You’re ashamed of the way you crouch behind the table’s pedestal on the floor with this man you hardly know as human armor, your arms around his back. His ribs begin to heave. You realize he is crying and you are sorry—so, so, sorry.

Your palms move to his breastbone, settle over his heart, one atop the other. The way you comfort yourself in the middle of the night when the waking dreams come. The shots grow closer, advancing in your direction. Curious, how calm your heart remains, fight or flight immobilized.

Everyone in your dream is you, you think.

And all at once you can feel the arms of the girl in the pink dress again, the lost child you’ve been searching for all these years, clinging to your back. Your daughter’s perfect hands, one atop the other, pressing against the slow waltz of your heart.

Suggested Reading

-

Flash • Nonfiction

-

Flash • Nonfiction

-

Flash • Nonfiction