Nobody Wants a Terrapin

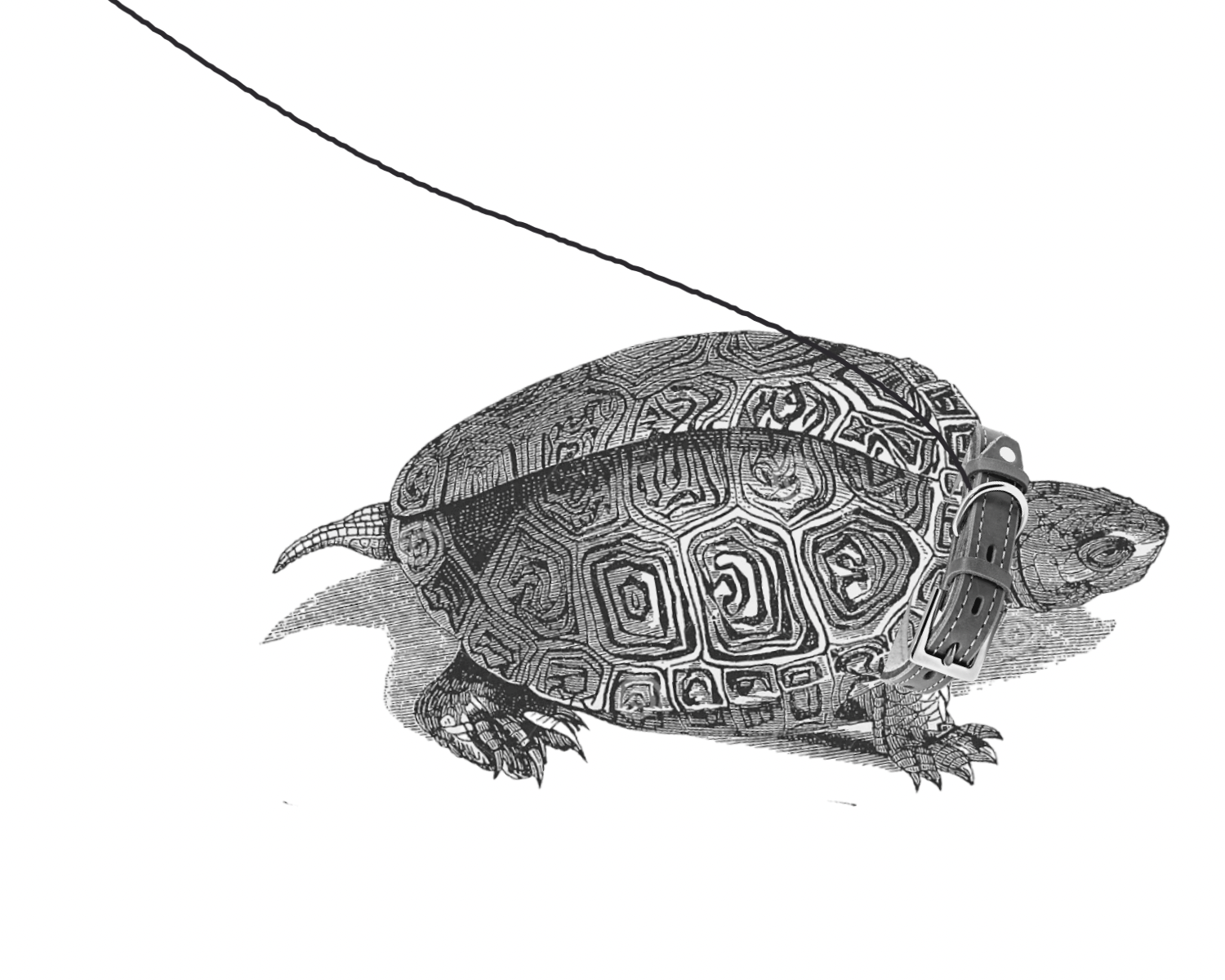

His life ended on the day when he chose to walk away from the terrapin. He remembered its shell, the patterns that swirled in circles reminded him of the growth rings of a fallen tree. A whole forest traced on the surface of a creature the size of a cobble. The terrapin’s shell fit perfectly at the bottom of the bucket but left no room to move. Its powerful legs wedged against the wall; its stumpy claws scratching against the smooth, black plastic. The terrapin stretched its long, crinkly neck up, trapped between the protruding shell and the hard wall pushing against the animal’s trachea.

Sergey watched the terrapin struggle to breathe: the creature’s beak opened wide, nostrils puffing. Of course, it could have retracted into its shell, but that would have left it stuck in the dark. Sergey understood – he also would have chosen to look at the sky through pain.

“They are vermin,” said a man in a hi-vis vest standing next to the bucket. He dragged at a roll-up while watching a group of men and women in the same hi-vis vests clearing the riverbank.

This was Sergey’s favourite spot on the common. The river curved gently between the steep bank on one side and a flat fragrant grassland along the towpath. He would take a stroll along the river every Sunday afternoon, his only day off. He told Tanya it was to focus his mind on the week ahead, but instead of fretting about his job, his thoughts almost always drifted elsewhere. He would invent things: a foldable ladder that you could put in a carry-on suitcase, or an invisible pen linked to the owner’s fingerprint. Or dream of being selected for the first space mission to Mars; what it would feel to explore its lifeless, red deserts. But, more recently, he imagined being back home. He would close his eyes and almost believe he was there – strolling across the vast expanses of untamed green rolling over the hills from his parents’ datcha, with not a hedge or another house in sight for miles.

He hoped that in just a few months, with no unforeseen expenses, they could book the flights for a visit. Hopefully, for the early autumn, when the air turns fresh in the mornings, but the days are still warm enough to take a swim in the lake. He felt the cool, crisp water against his skin, held his breath and imagined diving into the deep blue and laying there in the underbelly of the land until the pain in his lungs forced him up to the surface. Hopefully, he’ll be there before his father has another stroke. Hopefully…

“What does it mean, vermin?” he asked, always keen to learn a new English word.

“Harmful,” the hi-vis man gave Sergey a strange look, “non-native to this country. Folks buy them as pets, then realise they are not much of a pet, not awfully cuddly and pricey to keep, so they chuck them in the river where these pests destroy the riverbed.”

Sergey reasoned that it was not the terrapin’s fault if it was made to live in the river, but decided against voicing his thought. Being too honest had got him in trouble before; like that time when he disagreed with Mr. Wilson and hasn’t had an easy working day since.

“So now what?” he asked.

The man finished smoking his cigarette, looked around, and tossed the butt towards the uncleared section of the bank. “We’ll move it to the community centre, keep it there for twenty-four hours in case someone wants to take it. Then, put it in the freezer.”

“Freezer?” Sergey thought he’d misheard.

“Terrapins are cold-blooded – it’s an easy death,” the man explained.

“But someone will take it, right?” Sergey felt anxious. He checked his watch, as if he was trying to estimate how long until a loving family in need of a terrapin will arrive. It was quarter past five in the afternoon and there was no family in sight.

“Doubt it,” the man sighed, eyeing up the uncleared section of the bank, “It’s like I told you – nobody wants a terrapin.”

Sergey looked down at the creature in the bucket. The terrapin looked back at him with its piercing, beady eyes. Its look said: that’s ok buddy, I know how it goes. My bad luck for getting caught in the river.

The terrapin was a strange creature, it belonged to another world: a sandy beach by a turquoise ocean next to a single palm tree or the lush green of Balinese mangroves like on the posters Sergey saw in the travel agent’s window.

He pictured himself as a terrapin owner. He’d never had the urge for a pet. It would be a different matter if they had children, but it felt perverse to bring a creature in need of love and affection into their home. Yet the terrapin did not crave love, only to live. Surely Sergey could provide for that?

Maybe. If Tanya agreed. At his parents’ house they had pets: a couple of barn cats and a dog chained outside, not counting the chickens and the livestock. That was different, of course; there was an abundance of space and a purpose to every animal. A voice in his head reminded him that he had to be practical. It had his wife’s deep, smoky tone, but it was also the voice of his parents, his friends, and his grandparents who lived through a great scary war and would never dream of entertaining such an idle idea.

“Do you want to take it?” the man asked.

“Oh no, I couldn’t,” Sergey muttered, edging away from the terrapin’s gaze. “I live in a flat.”

The man shrugged and walked off to join the others by the river.

“Couldn’t you at least find a bigger bucket?” Sergey exclaimed, but the man carried on walking.

#

“But why not?” said Sergey. His voice came out high-pitched. He cringed at the sound of it, looking anxiously at Tanya who was busy getting ready for a shift. They’d spent the night arguing, but he thought he ought to give it another try in the morning. They’d argued a lot recently, mostly about the small things, sometimes about the important things and almost always when he brought up his father’s health or tried to budget for the next visit home. Tanya would cry, he’d apologise, and they’d carry on. It was difficult to deal with the important things, but today it was simple – he wanted to adopt a terrapin.

He watched the protruding arch of her back, as she pulled up her white stockings, careful not to ladder the flimsy fabric. In the last couple of years, her shoulders began to arch ever so slightly, weakening the posture that used to be exceedingly straight.

“Jesus, Sergey, you know we can’t have a pet!”

“But why the hell not?” he lowered his voice, but it somehow made it sound worse – almost comical.

This was not the best time to ask Tanya. Putting on her uniform always made her irritable. A long, baggy dress of watery blue did not suit her; its cheap material was too tight around her breasts and the crinkles would not come out even after the dress had been steam-ironed. And she used to love fashion! Back in high school, in their snowy, breeze block-built town, she was the best dressed girl in their class. Now, a cheaply framed picture on the windowsill stood as a sole reminder of that distant time and her first beauty.

“My last place, Rosewoods Court, had a couple of terrapins. They need a huge terrarium, some fancy heating system. Nightmare to clean,” she looked around with a sigh. “And where would we put it, in this shoebox of ours?”

He glanced around the living area: an old fake-leather couch pushed against the window, a stained coffee table (now used more often as a base for a clothes airer than an eating surface), a flat-screen TV facing the couch from a small kitchenette sideboard, leaving only a narrow pathway to the ensuite bedroom. She was right – they lived in a tight space. This may have been the first time he’d really cared enough to notice it. He shivered, suddenly struck by how cold he was in their home.

“We could get rid of the coffee table: we never use it anyway,” he haggled. “You’ll see, it’ll free up lots of space!”

He approached her slowly, hugging her from behind, the arch of her back fitted perfectly along the groove of his ribcage. Resting his chin on her shoulder he proceeded to rock her gently in his arms, like during their first dance at the school disco; or, years later, on their wedding day to the sounds of slow waltz. How happy they were back then, how hungry for their future together. She’d wanted a new life far away; he chose to join her.

She shoved him aside with surprising force.

“I swear to God, Sergey, sometimes you are worse than a child.” She smoothed the rough fabric over her hips, rucked up by his touch, in fast, jerking movements. He felt sorry for the old who had to endure the touch of his wife’s tough, merciless fingers. One day, he’ll grow old, maybe in this tiny flat; he will slump on the couch facing the kitchenette and will grow to rely on those very fingers.

He felt something important snap inside him, the twang was almost physical. “If we were back home, we could have a bale of terrapins.”

“I am not having this conversation again, Sergey.”

“But why not?” he sounded like a broken record, he also felt like one.

“You’re a dreamer Sergey. You idealise things. In your head, every day was a Sunday with games and ice-creams. But I remember the Mondays with no central heating, no running water and a three-mile hike to the nearest shop. Is that the kind of life you want for us?”

“Terrapins are great pets for children.”

“Then it’s lucky we don’t have any.”

“We could.”

This was not the argument he was planning to revive. That argument was dead, withered like an ancient mummy and stuck in the closet where it would always remain out of sight, yet never buried. He sighed, “Look. All I want is a terrapin, is that so much to ask?”

“You can’t have one.”

“Then what’s the point?” he snapped. “What’s the point in your central heating and your shops and your Mondays? What is the point in carrying on living like this?”

“Oh, I didn’t realise it was such a torture for you,” she laughed. “Of course, we can set up a zoo in the house, if that will make you happy.”

“I am rescuing it. And I don’t care what you think,” he said.

A flash of surprise rose in her face before she gathered herself and headed for the door.

“God almighty,” she groaned, fishing for the car keys in a coloured, glass bowl, “I’ve had enough. If you pick up that filthy animal – don’t bother coming back. It’s your choice.”

It was his choice, and yet he felt that he was left with no choice at all.

The door shut softly behind her watery blue figure. She was not prone to dramatic outbursts like slamming doors or shouting obscenities from windows for the neighbours to eavesdrop. She was a woman of steady, controlled temperament. That’s how he knew that she had meant every word.

#

The canteen was jam-packed with tired, gloomy men wishing to be left alone.

“No walking in the rain or having to worry about it ripping the furniture,” Sergey persisted. “None of that fur to clog the hoover – they are nice, clean pets.”

“Mm,” Steve was too busy with a sausage roll to engage. The lunchtime was only half an hour before they had to return for another stint at the conveyor belt.

“Think about it, it’s only four months until Christmas – you could get away without spending a penny,” he continued, despite his mild dislike for the guy.

There was nothing wrong with Steve as such, but Sergey always felt repulsed when they spoke. Like now, he couldn’t imagine why would anyone want to eat a sausage roll at the meat processing plant; it was too much like that joke about a hooker who got herself a job at Amazon because she loved to handle large packages. But after spending all morning hopelessly selling the terrapin dream to every man on shift, Steve was Sergey’s last hope. At least he’d expressed some interest. Aright, I’ll text my missis, he’d mumbled an hour earlier, but hadn’t said a word since. Sergey grew impatient.

“You’ll need to leave early to pick it up.”

“What?” Steve dealt with the roll and proceeded to lick his fingers.

“The terrapin!” cried Sergey.

“Nah, missis says they stink.”

Sergey got up and left the canteen, stopping by the locker to pick up his jacket when foreman Wilson spotted him.

“I have to leave early, Mr. Wilson.”

The foreman grinned, “Got a leave booked?”

“No.”

“Can’t leave then.”

Wilson was after him ever since their disagreement a few months ago when Sergey expressed an opinion that Mr. Wilson had been a petty prick for not letting one of the lads swap shifts to go for a ten-week scan with his wife – Mr Wilson disagreed. Sergey could attempt excuses: a family emergency, wife at a hospital, fire at their flat, stomach troubles from last night’s takeaway, but it would be no use, and he did not want to lie, pretend, bargain or reason with Mr. Wilson. And why should he? There was a terrapin to be saved and anyone who was not prepared to accept it as a good enough excuse was not worth speaking to.

“I’m sorry, Mr. Wilson, but I have to go.”

“Leave now and see if you will be let through the gates tomorrow. Your choice,” he shrugged.

As Sergey left the fuming, and somewhat confused foreman behind, he felt saddened by the encounter. Mr. Wilson, like Sergey’s wife, was not the type to change his mind. Leaving now meant he would not get to choose to come back. Yet, the terrapin did not choose to be abandoned in the river, it did not choose to be caught and left to suffocate in a small bucket.

He would rescue the terrapin. They would go to a place that was not foreign, with lots of green, where every day was a Sunday – as long as they got there before early autumn. Or they could travel to the mangroves, visit the lonely palm tree from the holiday posters. They would figure it out. Sergey was not egoistical in his plans: he knew the terrapin and he were in it together. Besides, the destination was not important, the important thing was that he wanted to save the terrapin. And he would.

#

The local community centre was nothing more than a rundown shack tucked away in the furthest corner of the common. It was built in the seventies, and there was a hint of the stale passing of time mixed into its beige wall paint and wine-stained furnishings. The building used to buzz with social clubs and exercise groups, but these days it was mostly known for its alcohol licence and cheap rental space.

It was just before half past three. He walked through an empty hall to a small room at the back, following the sounds of a TV switched to full volume. The man was at the back. Having swapped his hi-vis vest for a pair of saggy joggers and faded Aston Villa T-shirt, he sat by a large flat screen armed with a family-size bag of Doritos and two cans of lager.

“I’m here for the terrapin,” said Sergey.

The man jumped, spilling some beer over his pants. “Ah, shh—,” he rubbed the liquid stain, then looked at Sergey, puzzled. “Today is match day,” he gestured towards the screen.

Sergey shrugged; he was not in the mood to watch football. Then, he looked into the man’s eyes, and he knew.

“People stay at home to watch. I didn’t think anyone would come today,” the man sounded apologetic.

In the corner of the room stood a large, commercial freezer. Sergey opened the bottom drawer and took out the terrapin. The patterns on its back had frosted over – the forest turned into a winter plain. The terrapin had finally retracted into its shell. Its head tilted to one side, the eyes were sunken and shut.

He pulled the terrapin out, feeling its weight, and wrapped it in his jacket, hoping that warmth could still fight off death, but the basic laws of nature were stacked against him. It was no use being angry, Sergey knew better than try to control nature. And as to people, weren’t they also part of nature?

He walked out of the community centre, cradling the jacket, not knowing where he was heading until he spotted a familiar bend.

The riverbank was entirely cleared, bushes trimmed, grass cut down to the brown stems. The area looked like a carcass of its former self, stripped to the basics – sterile. He placed the terrapin carefully in the water, reasoning that no one could object now it could no longer fight for its right to survive in this strange land. Terrapin’s body sunk to the bottom, weighed down by its heavy shell, and made no waves.

He sat by the river for a long time, watching its smooth surface. Somewhere far away, in another cosmos, Tanya was paying a locksmith, Steve headed to watch the game with Mr. Wilson, the hi-vis man had changed into a fresh pair of joggers.

Sergey kept revisiting the day when he’d walked away from the terrapin; everything before that day was already dead, all because he had made a wrong choice, but today, sitting on the bare riverbank, he knew there would be more. He had a whole life full of possible choices, he felt privileged.

Suggested Reading

-

about Lollipop, Lollipop![Lollipop]()

Featured • Fiction • Nonfiction

Lollipop, Lollipop

The figure moved slowly, deliberately, its shrouded head turning towards Josh. Those eyes—sharp and frigid as icepicks—stared at him. The man’s black lips never moved, even as a word pierced him like a yell: “Beware.”

Featured • Fiction • Nonfiction

-

Featured • Fiction

-

Fiction